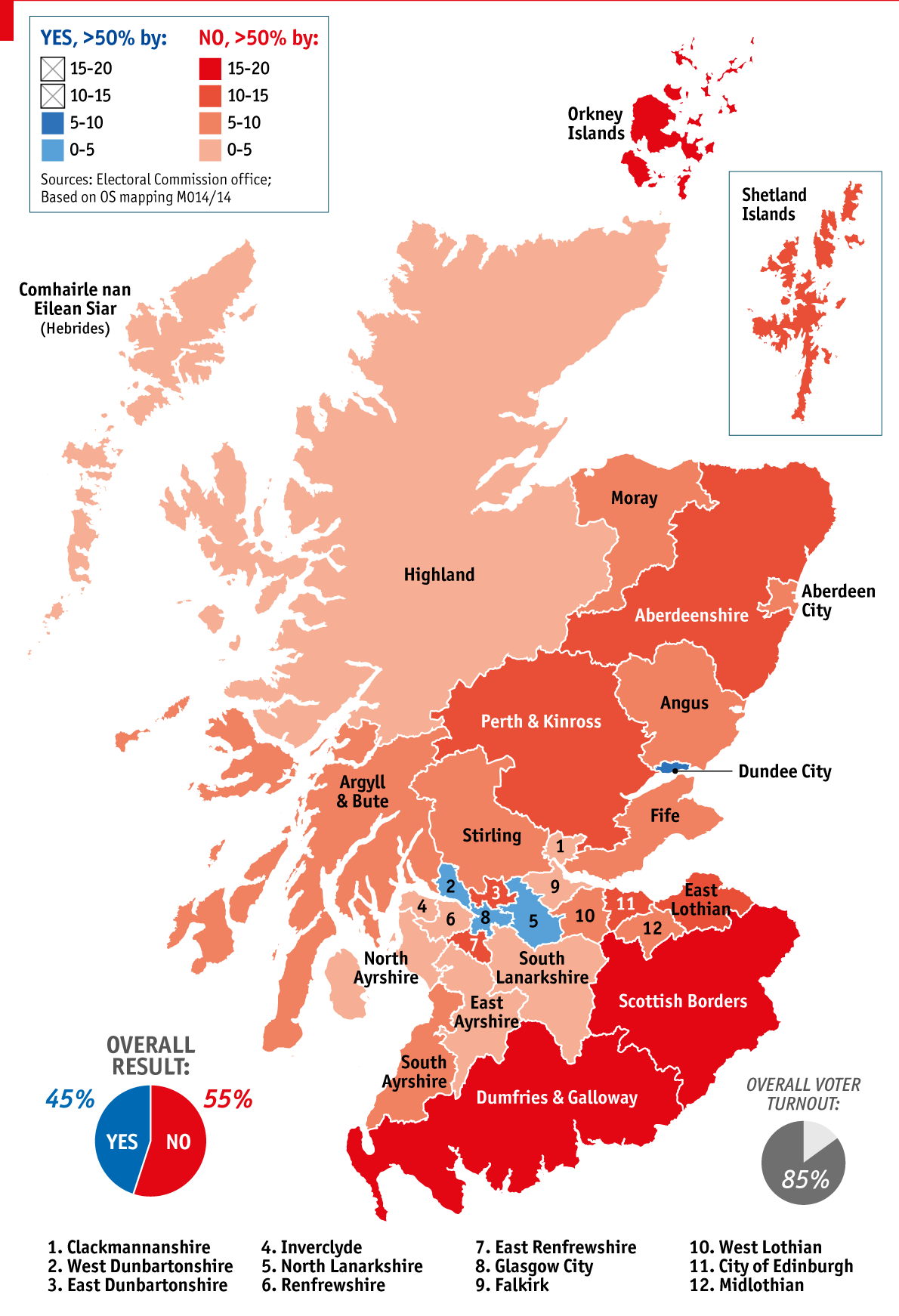

Yesterday, Scotland voted on its independence from the United Kingdom. Early this morning, the ballots were counted. By a margin of 400,000 votes, Scotland voted 55-45 to remain within the UK.

I collected my tweets from last night, which showed history as it happened — the vote totals as they came in (retweeted from the BBC), commentary from journalists in Scotland, and some of my own commentary. It was, as I said somewhere along the way, a bit like Monty Python‘s “Election Night Special” sketch.

Unlike some Americans, Scotland’s referendum on independence did not come as a surprise. I remember when Alex Salmond’s Scottish National Party won an outright majority back in 2011 and following the negotiations for the Edinburgh Agreement that laid out the framework for this independence vote. Initially, I was in favor of Scottish independence, not for any political reasons but for romantic reasons — who doesn’t dream of an independent Scotland, free from the shackles of England? Then I read the white paper on independence produced by the Scottish National Party, and my romantic dreams began to give way to more practical concerns about how Scotland would work as an independent nation. Ultimately, I came down firmly on the side of the No campaign. I wanted Scotland to remain within the United Kingdom.

The issue of Scottish independence has multiple causes, and I don’t know that I could go into all of them — or even that I know all of them. At the fundamental root, Scottish independence has a lot in common with populist movements — there’s a distant, central government that doesn’t understand our needs, so something Must Be Done. In some cases, like the 19th-century Populist Party or the 20th-century Progressive Party or the 21st-century Tea Party in American history, the populists attempted to reform the system by getting into positions of power and working from within. The Scottish Nationalists took a different tack; they wanted to sever their ties to the distant government in Westminster, they wanted to undo the Act of Union 1707. In The Atlantic yesterday, Katie Engelhart compares the Yes campaign to Occupy Wall Street. That strikes me as a fair comparison; Scotland’s politics are center-left (there are more panda bears in Scotland than Tory MPs, so I’ve heard), while England’s politics run center-right. There was the perception in Scotland that the status quo wasn’t working. More importantly, the perception was that the status quo could never work.

Despite the decisive loss by the Yes vote, Alex Salmond, Scotland’s First Minister, the head of the Scottish National Party, and the face of the Yes campaign, still won. He moved the needle on independence in Scotland from the level of the unthinkable (it was thought to hover around 30%) to the thinkable (his 45% share of the vote yesterday). More importantly, he got what he wanted all along — promises from Westminster to pursue Devo-Max. In Salmond’s negotiations with Cameron in 2012 over the referendum, he wanted three options — Independence from the UK, Devo-Max, or Remain in the UK. Cameron wanted only two. Devo-Max was a middle option — greater autonomy for the Scottish Parliament and greater self-rule for Scotland — but David Cameron wanted an all-or-nothing question on the assumption that the question wouldn’t be close.

But it was close. Closer than anyone six months foresaw. Far closer than Cameron expected when he agreed with Salmond two years to permit the referendum. What happened?

Turnout, no doubt, has a great deal to do with it. There was an incredible 85% turnout for this election. Cynically, it’s dictatorial regimes that see turnout numbers that high in elections that we would call anything but free. Yet, here was a country going to the polls, in droves, to vote freely on their own future. Scottish independence was an issue that touched the souls of the Scots. The issue drove turnout.

The message also had something to do with it, especially the message from the Yes campaign. Salmond offered a message of hope, that Scotland could stand among the countries of the world, that Scotland could be self-sufficient, that Scotland could shape its own future. It’s an inspiring vision. And frankly, it’s a difficult vision to counter. If the voting population already feels that the status quo is unfair to them, arguing for the status quo, especially for an unpopular Tory government in Westminster, and against the allure of hope is difficult. If Westminster has failed Scotland (or has the perception of failing Scotland), it’s hard to argue that a failed Westminster can suddenly find the wherewithal to help Scotland. The Yes campaign argued that things would be better, usually in the “best case scenario” way, while the No campaign was limited to negative implications of the Yes campaign. This made for an odd, if rhetorically mismatched, campaign — Yes argued for aspirations, No argued for practicalities, and they weren’t always playing on the same territory.

The polling on the referendum was fascinating. Some would say that there’s not a great deal of difference between the final YouGov poll (an eight point spread in favor of No) and the actual result (a ten point spread), but what I find especially notable is how the Yes campaign underperformed in areas where they expected to be much stronger. They expected a thirty point victory in Dundee and got half that. Yes lost Comhairle nan Eilean Siar by 1500 votes; Yes expected that to be firmly in their column. Quite simply, if you went by the polls, the vote should have been closer than ten points. I was discussing this on Twitter last night with a friend in the UK as the early returns came in. I suspect that what we saw was not unlike the Bradley Effect in the United States, a well-known phenomenon where African-American candidates for office underperform their polling expectations. I suspect that we could have seen a similar effect in polling in Scotland, especially two weeks ago where the Yes campaign topped the No campaign in polling for the first time. Perhaps, surveyed voters told pollsters they were going to vote Yes because they didn’t want to feel stigmatized for their real No leanings. Perhaps they felt like they should be nationalistic in conversation with the pollster. Or, the polling simply could have been bad altogether. Alberto Nardelli looks at the polling issue in The Guardian, and he reaches similar conclusions; no matter the cause, Yes underperformed to expectations.

Part of me would like to ascribe the underperformance to Gordon Brown’s fiery entry into the fray. Perhaps the intervention of the former Prime Minister did turn some votes. Perhaps his political rehabilitation saved the UK. I’ve always liked Gordon Brown for some reason; he’s awkward and cranky, perhaps a little too prone to anger, and fiercely intelligent. Brown came out forcefully in favor of the No campaign, and for the final few weeks he was the face of a unified Britain. His barnburning speech on Wednesday, where he roused “the silent majority” to stand up for the United Kingdom was a piece of brilliant oratory, fierce and powerful. Cameron may well campaign in the next general election as the Prime Minister who saved the UK, but history will show that it was the former Prime Minister, Gordon Brown, who actually managed that feat.

Part of me would like to ascribe the underperformance to Gordon Brown’s fiery entry into the fray. Perhaps the intervention of the former Prime Minister did turn some votes. Perhaps his political rehabilitation saved the UK. I’ve always liked Gordon Brown for some reason; he’s awkward and cranky, perhaps a little too prone to anger, and fiercely intelligent. Brown came out forcefully in favor of the No campaign, and for the final few weeks he was the face of a unified Britain. His barnburning speech on Wednesday, where he roused “the silent majority” to stand up for the United Kingdom was a piece of brilliant oratory, fierce and powerful. Cameron may well campaign in the next general election as the Prime Minister who saved the UK, but history will show that it was the former Prime Minister, Gordon Brown, who actually managed that feat.

Salmond announced this afternoon that he would step down as Scotland’s First Minister and head of the SNP in the wake of the referendum’s defeat. This came as a surprise; I expected Salmond to remain in the fray, hammering out the new devolution settlement that the Westminster parties promised in the last two weeks. The politician whose career I thought could end because of the referendum was Cameron’s; he would have been the prime minister to bungle Scotland so badly as to lose it from the United Kingdom. In Salmond’s absence, someone will have to hold Westminster’s feet to the fire; despite the statements by both Cameron and Salmond that independence is off the table for a generation, I suspect that if nothing is forthcoming from Westminster on “the devolution revolution,” then Scotland will be back at the independence question in a decade.

I don’t know what “the devolution revolution” will look like; that’s a question for all Britons to determine. The actor Brian Cox was on the BBC World Service’s Newshour earlier today, and when asked his opinion, he ventured that a federal UK was the only real solution. Matt Ford writes about British federalism in The Atlantic — “with Cameron calling for a ‘devolution revolution’ and [Labour leader Ed] Miliband inching toward a written constitution, the future of the U.K. looks increasingly like a United States of Great Britain.” Perhaps a federal legislature in Westminster for the four kingdoms — England, Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland — that handles issues of critical importance to all four, such as defense. Meanwhile, each would have a parliament of their own for issues of local import. In other words, perhaps a federal UK would look a bit like the United States. But this would be radically different than anything the United Kingdom has ever known. And it might be too radical for Britain. To the outside observer, devolving powers seems like the simple and logical solution. But to those who have power in the current system, a federal United Kingdom might well mean giving up a great deal.

Even though I would have been happy with either decision, I am glad that Scotland voted to remain part of the United Kingdom. Scotland was given a choice to determine its own future. Plus, the referendum made everyone around the world talk about Scotland, at least for the last two weeks. It wasn’t just a place on the map. It was a place filled with people with dreams and aspirations. I think we lose sight of that. Not with Scotland specifically. Rather, I think we lose sight of the fact that there are seven billion people on this planet, that there are more countries and more peoples than we can count — or even realistically remember — and every person is important. Every person has dreams and desires.

In Scotland, yesterday, nearly two million people dreamed of independence.