What if the Beatles didn’t get a record contract with Parlophone in 1962?

That’s the subject of BBC Radio 4’s radio play, Sorry, Boys, You Failed the Audition, adapted by Ray Connolly from his novella of the same name. Originally broadcast by the BBC in 2013, it was rebroadcast again this week, and I streamed it at work this afternoon.

I have two reactions to the radio play, one as a work of fiction and drama on its own terms, one as a speculation on the Beatles and their history. (I should note that I have not read Conolley’s novella, though I have now bought it for my Kindle.)

Let’s talk about this as a piece of drama first.

As a piece of drama, on its own terms, Sorry, Boys, You Failed the Audition ia enjoyable. Told from the perspective of Freda Kelly, their official fan club chronicler in their Liverpool days, the Beatles fail to secure a recording contract and, having reached the limit of where they could go as, essentially, a Liverpool bar band, they go their separate ways — John Lennon marries Cynthia and becomes a comic writer, Paul McCartney goes to college and becomes a school teacher, George Harrison stays in music and becomes something of a session guitarist, and Ringo Starr disappears. Freda is the play’s narrative viewpoint and central character, and she is determined to carry on chronicling their post-band exploits. Just when she’s ready to pack it in, after a few years of carrying the Beatles’ flame, something happens that gives her a new purpose in life — to reunite John Lennon and Paul McCartney as songwriters, and maybe the rest of the band, too.

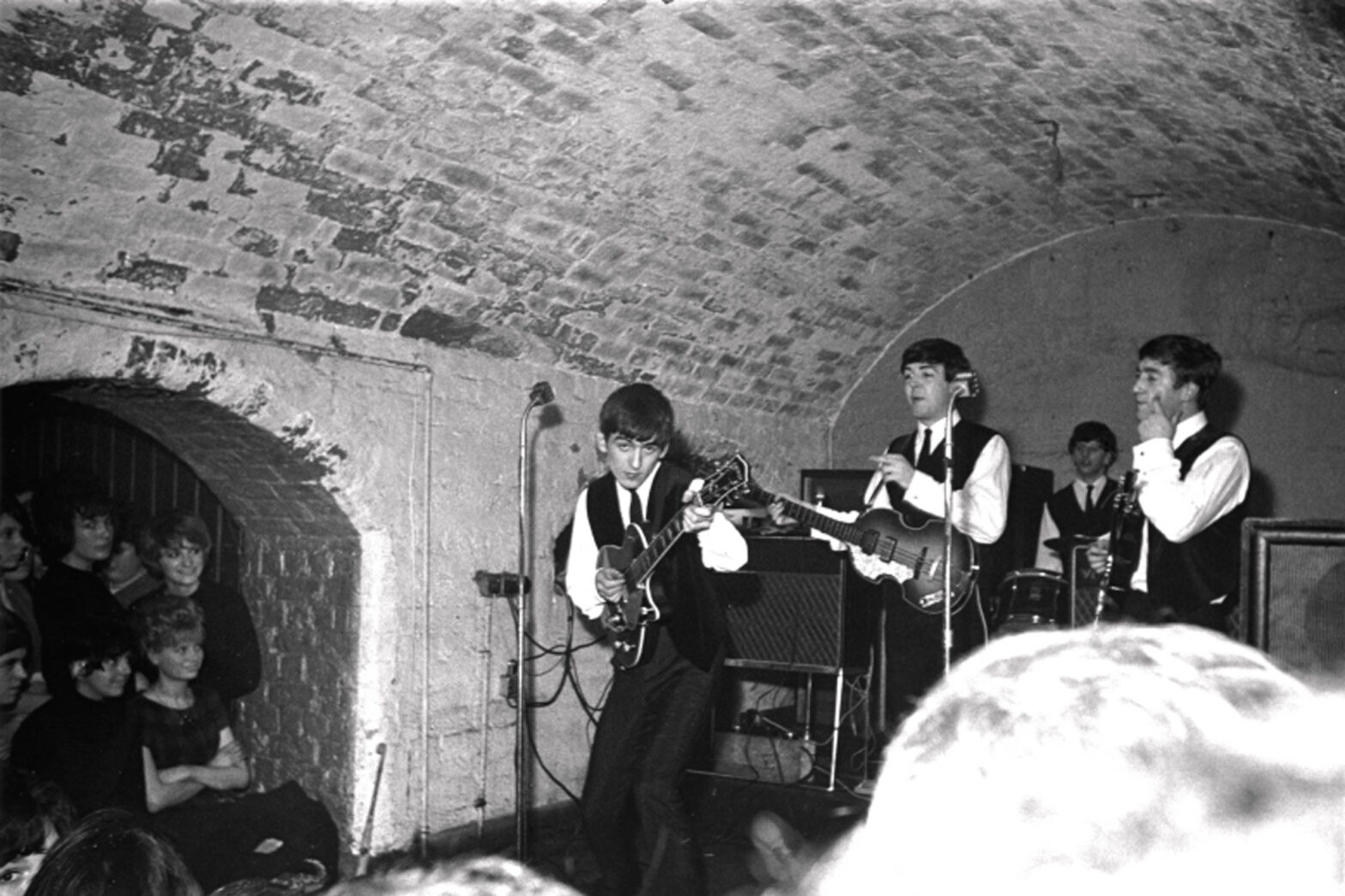

It’s a cute radio drama, and Sara Bahadori’s Freda Kelly is a charming and captivating narrator. The Beatles voices sound generally right, and the characterizations of the Beatles, even in a world without the Beatles, ring largely true. The end of the play, on a cold morning in January, 1969, isn’t at all surprise, and despite that lack of surprise I had a grin on my face when it happened. I was impressed with the production of the play; Beatles songs are used at several points in the play to give it a sense of verisimilitude such as in its recreation of the Cavern. It was entertaining and fun to listen to, and I think Sorry, Boys, You Failed the Audition is worth listening to.

Now, let’s talk about this as a work of Beatles speculation.

As a piece of alternate history, I’m critical of it. Every few minutes, it would do something that didn’t strike me as quite right.

As alternate histories go, this is really, completely improbable

— Allyn Gibson (@allyngibson) December 11, 2015

I had three basic problems here — the 6 June 1962 EMI session, Ringo Starr, and the butterfly effects. I’ll take each of these in turn.

At New Years 1962, the Beatles auditioned for Decca Records in London. The Beatles were turned down; Decca famously said that “guitar groups [were] on the way out.” Beatles manager Brian Epstein then used the Decca recordings (of which he had an acetate made) to attempt to get the Beatles in the door elsewhere. In this, he proved successful — eventually, the Beatles came to the attention of EMI and Parlophone producer George Martin.

It has commonly been believed that the Beatles first session with EMI at Abbey Road Studios on June 6, 1962 was an audition. The Beatles themselves certainly believed that. However, that’s not what EMI’s paperwork indicates; George Martin signed the Beatles without an audition through something of a circuitous process, as Mark Lewisohn documents in Tune In, yet the play’s point-of-departure turns on the common myth that what was, in fact, their first recording session was an audition. To be fair to Ray Connolly, Tune In was published at about the same time this play was originally broadcast, and had the Beatles not impressed at the time Martin and Parlophone would have been able to cut them loose quite easily, so he does have some justification for turning history on the myth rather than the reality.

Less justifiable is the presence of Ringo Starr in the story. At the time of the June 6 session, the Beatles’ drummer was Pete Best, and he was yet to be sacked and replaced by Starr. (In our history, Best was dismissed by the Brian Epstein, at the behest of the other three Beatles, on August 16th.) The Beatles were certainly friendly with Starr — they crossed paths on a number of occasions in Liverpool and Hamburg, and Starr was certainly the most accomplished and sought after drummer in Liverpool at the time — but he wasn’t part of the band as of the June 6 EMI session.

You can almost sidestep these problems if the point-of-departure for the story comes after the September 11, 1962 recording session at EMI which, if I’m remembering Tune In correctly, fulfilled their initial EMI recording contract, but the play’s initial scene and the Beatles’ recollection of their “audition” better fits the June 6 recording session. The reason I say “almost” is that, even if you make that one change to the story, Ringo still would have been a Beatle for only a month which makes later events for Ringo less likely than they are in the story.

Or the point of departure is much earlier, say immediately after the Decca audition. Perhaps the band sacks Pete Best in early 1962, and the knock-on effects of that — Ringo instead of Pete — causes the June 6 session to go badly, which causes George Martin to write the Beatles off as a loss, which leads to the start of the play. This scenario might work.

This brings me to my third problem — the butterfly effects. To me, the world Freda Kelly inhabits in Sorry, Boys, You Failed the Audition seems a bit too familiar. Groups like The Rolling Stones and The Moody Blues exist in forms that we would recognize — we hear one of the Stones’ early recordings at one point — sidestepping the whole issue of the extent to which British music was a reaction to the Beatles. (For a really good look at this, especially as it relates to the Stones, see John McMillian’s book, Beatles vs. Stones.) I found it especially questionable that George Martin would be looking for — or even be in a position to be looking for — a band like the Beatles in 1969 in a world where the Beatles didn’t make it. As a poetic, artistic statement, I understood that creative decision; as a matter of history, I’m quite skeptical.

I’ve just eviscerated something that I enjoyed. As a writer myself, I understand that there are times where you don’t let the facts stand in the way of your story. I totally get what Connolly was doing with Sorry, Boys, You Failed the Audition. He found a unique angle to explore the Beatles’ break-up and what it felt like, as a fan, to want to see them back together.

Let me explain this thinking.

It’s notable that, in the play, it’s John who leaves the band first, and the other three attempt to carry on without him. In the summer of 1969, it was John who announced that he was leaving the band, leaving the other three to decide what they wanted to do, and they did record together without John one track for Let It Be — “I Me Mine.”

John becomes something of a house husband, as he did in real life. Paul continues to write music; in real life, he was by far the most prolific of the ex-Beatles. George becomes a session man with a passion for gardening, not unlike his own post-Beatles career. (George seemed to like being a background guitarist.) And Ringo was laid back and unambitious, which describes Ringo’s last thirty years. (This is not a knock on Ringo; I really like his solo output since Time Takes Time, but he’s doing it because he enjoys it, not because he trying to top the charts or be a name.)

Freda, when she decides to get John and Paul back together, annoys them with her incessant questioning, just as the Beatles themselves were annoyed by fans and reporters over the years asking them when they were going to get back together. Then, John and Paul have a moment, in the play, that’s not unlike the 1974 Los Angeles jam session with John and Paul during John’s “Lost Weekend,” albeit a moment that turns out to have more lasting consequence than the Los Angeles session. (Is the difference here that John was married to Cynthia instead of Yoko Ono at the time? I have to wonder…)

My point is, you can read the play as a commentary on what it was like to be a Beatles fan in the 1970s, wishing and hoping for the band to get back together, told instead through the prism of the 1960s as seen through the eyes of their most dedicated fan. In that sense, Sorry, Boys, You Failed the Audition is really quite unique and interesting, and the historical criticisms I have are wholly beside the point.

I enjoyed it more than Stephen Baxter’s “The Twelfth Album,” that’s for sure. 🙂

If you at all like the Beatles, give Sorry, Boys, You Failed the Audition a listen. It’s fun, Sara Bahadori’s performance as Freda Kelly is captivating and winsome, and the whole thing is enjoyable. I really did like it.