A few months ago on a bulletin board I was drawn into a somewhat tedious argument over what, exactly, pipeweed is in The Lord of the Rings. My sparring partner argued that pipeweed was clearly tobacco, Tolkien said so, and that, clearly, was that.

The problem with the identification of pipeweed with tobacco, I said, was this:

Middle-Earth is not a fantasy world. Instead, Middle-Earth is our world, albeit in a far-distant past that is no longer remembered, and The Lord of the Rings is not a novel but is instead a written account, a memoir even, by some of the participants in the War of the Ring. Eregion, the region of Middle-Earth where The Hobbit and much of The Lord of the Rings takes place, corresponds to northern Europe. Since tobacco was unknown to Europe prior to the sixteenth century, then pipeweed cannot be tobacco. (The same argument applies to the potatoes that Sam cooks; they could very well be a tuber, but they’re not our potatoes.) This doesn’t mean that Tolkien was wrong in his identification of pipeweed with tobacco. It just means that Tolkien either unintentionally mistranslated the Red Book of Westmarch or he translated the idea given in the Red Book in a way that modern audiences would understand.

If you’re a Sherlock Holmes fan of the old school variety, you will instantly recognize the argument I’m making here. This is the Game. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle didn’t write the stories, he was the literary agent for the real author, Doctor John H. Watson. And everything that Watson wrote was based on true events, even when it contradicts itself, which places the actual truth of the events at a slight remove from Watson’s accounts.

All of Tolkien’s talk of the Red Book and its history lends credence to this kind of reading of The Lord of the Rings, as does the strange reference made to locomotive trains in “A Long-Expected Party,” which is not a phrasing that would have been in the Red Book of Westmarch but is the kind of reference a translator would use to make an obscure idiom comprehensible.

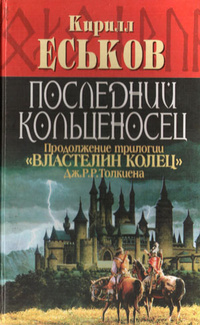

This was the kind of thought I kept in mind over the past two weeks as I read Kirill Yeskov’s Russian sequel to The Lord of the Rings, The Last Ringbearer.

This was the kind of thought I kept in mind over the past two weeks as I read Kirill Yeskov’s Russian sequel to The Lord of the Rings, The Last Ringbearer.

I learned of Yeskov’s novel a year ago when Salon reviewed it after an English translation appeared online. I printed it out and tried reading it then. I read several chapters, but my attention was drawn elsewhere and I left it unfinished. Then I learned there was an updated translation, and I decided I could try reading it on my phone’s Kindle app, so a few weeks ago I downloaded the revised edition and gave it a go.

Yeskov calls The Last Ringbearer an “apocrypha,” but the word “sequel” works just as well, though I suppose, technically, The Last Ringbearer is a midquel that chronicles five months, beginning with the Battle of the Pelennor Fields, as seen from the perspective of two Mordorian soldiers (Field Medic Haladdin and Sergeant Tzerleg) and a Gondorian nobleman (Baron Tangorn), and it recounts their adventures in the immediate aftermath of the War of the Ring.

If The Lord of the Rings is the story of the War of the Ring told from the perspective of the Hobbits in the style of a medieval romance, then The Last Ringbearer is the story told from the perspective of Mordor’s foot soldiers in the style of Tolstoy and (surprisingly) Ian Fleming. One version of the story is mythologized and romanticized, the other version draws upon history and realpolitik.

That’s what The Last Ringbearer is. Now, is it any good?

As a book of ideas, The Last Ringbearer is fascinating. Yeskov grapples with a number of problems in Tolkien’s story that Tolkien never addressed, probably because they never occurred to him. To whit — What were the war aims of the belligerents in the War of the Ring? How did the economies of Middle-Earth work? What kind of civilization could Mordor support? Yeskov examines the history and geography of Middle-Earth, and he extrapolates from them some logical conclusions. As an example, Yeskov theorizes that Mordor went to war against Gondor not to subjugate the world but simply to secure the grain shipments from the south that were necessary to feed its people, since the blasted arid landscape of Mordor would make it impossible for Mordor to be self-sufficient.

As a book of ideas, The Last Ringbearer is fascinating. Yeskov grapples with a number of problems in Tolkien’s story that Tolkien never addressed, probably because they never occurred to him. To whit — What were the war aims of the belligerents in the War of the Ring? How did the economies of Middle-Earth work? What kind of civilization could Mordor support? Yeskov examines the history and geography of Middle-Earth, and he extrapolates from them some logical conclusions. As an example, Yeskov theorizes that Mordor went to war against Gondor not to subjugate the world but simply to secure the grain shipments from the south that were necessary to feed its people, since the blasted arid landscape of Mordor would make it impossible for Mordor to be self-sufficient.

This is very much of novel of politics, and much of the drama revolves around the interactions and the jockeying for position between the various powers, even among ostensible allies. The third section of the novel, “The Umbarian Gambit,” takes the action to the city of Umbar, and Yeskov’s Umbar is not unlike Istanbul — a cosmopolitan city caught between two great empires. Here the novel takes an interesting turn and becomes a gripping spy novel, as spy network grapples with spy network and no one’s quite sure who they can trust.

As a book of plot, The Last Ringbearer is adequate. Haladdin and Tzerleg (the latter what Tolkien would call an Orc and what Yeskov calls an orocuen — simply a nomadic tribe of men that live on Mordor’s plains), in their retreat from Mordor, chance across a Gondorian soldier left for dead by an Elven party. They join forces with no real goal in mind, and soon they are recruited by one of the Nazgul to find a way to destroy Galadriel’s Mirror and end all magic in Middle-Earth.

Conceptually, this is an interesting hook. A Tolkien fan might protest, “But didn’t the destruction of the One Ring end magic in Middle-Earth? How can there still be Nazgul after the fall of Sauron?” And Yeskov offers answers for those questions. The execution of the plot, though, is occasionally frustrating. It’s clear by the end of the first part how Galadriel’s Mirror will be destroyed, but it’s never really clear how the actions of the protagonists will lead to that. As fascinating as “The Umbarian Gambit” is, there’s a crucial piece of information that’s missing that makes it work. Much of the plotting is entirely coincidental, and the final quarter of the book simply isn’t that interesting. The ideas are good, the hook is good, but the execution falls a little short.

As a book of writing, The Last Ringbearer is a fan’s translation into English of a Russian text. Occasionally, the prose soars, like in this much quoted description of Barad-Dur from chapter two: “that amazing city of alchemists and poets, mechanics and astronomers, philosophers and physicians, the heart of the only civilization in Middle Earth to bet on rational knowledge and bravely pitch its barely adolescent technology against ancient magic.” But then there’s a strange tendency for the verb tense to randomly shift in the middle of the paragraph, and the less said about the dialogue the better; only Jersey Shore uses the word “guys” more often than the translation of The Last Ringbearer. I found myself mentally editing the book as I read it to fix the temporal problems and the dialogue. Neither were particularly irksome, but they marred the overall effect.

As a story of Middle-Earth, The Last Ringbearer is compelling. It’s not Tolkien’s work, but it still manages to be valid as a vision of what the remote past was like. Yeskov’s Aragorn is, frankly, an asshole, but it’s not a jarring characterization; Frodo Baggins, the writer of the Red Book, had a reason to idolize Aragorn and wrote as such, while Tzerleg, on whose accounts The Last Ringbearer is based, had a different perspective. Faramir and Eowyn are the “canonical” characters with whom we spend the most time in The Last Ringbearer, and they’re not far removed from the version we see in Tolkien. The comparison I keep making is to Monty Python and the Holy Grail; Tolkien’s account of the War of the Ring is like King Arthur, who received by divine providence a sword from the Lady in the Lake as a sign of his fitness to rule, while Yeskov’s account of the same events is like the anarcho-communalist syndicate, who question anything and everyone and think that swords handed out by strange women in ponds are not a sound basis for government.

That actually makes sense in my head. I’m not sure it comes out correctly on the screen.

Obviously, I’ve thought a great deal about the ideas of The Last Ringbearer since finishing it last night. But what did I think about the book itself?

I’m glad I read it. I enjoyed it. The Last Ringbearer took me to one of the most vividly realized places in Middle-Earth — the city of Umbar — and it introduced me to some characters, particularly Baron Tangorn, that I wish had made it into the Red Book of Westmarch. It was a page-turner, in the electronic sense, anyway, and I was genuinely curious how it would turn out. The main thing, I don’t think The Last Ringbearer does anything that gets the story we know “wrong.” It makes different assumptions, it puts a different emphasis on things, but by and large it springs out of a story we know and says some fascinating things about that time and place. It’s not the sequel to The Lord of the Rings that most people would expect, but that only makes it that much more interesting. Kirill Yeskov’s The Last Ringbearer tells its own story, and in so doing it deepens our understanding of a familiar world.

Originally published here.