Be warned. This post contains spoilers for a three year-old film based on a decade-old book.

Be warned. This post contains spoilers for a three year-old film based on a decade-old book.

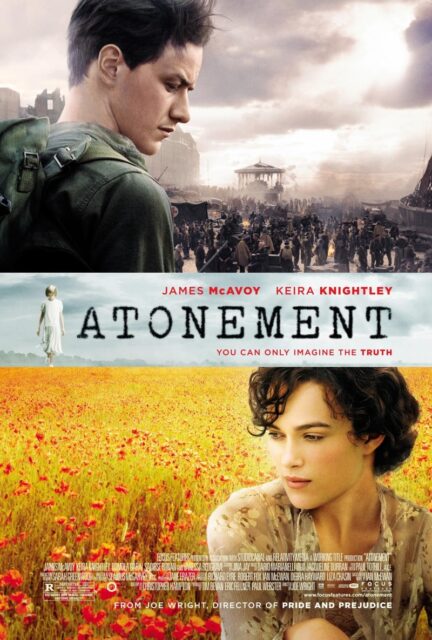

Tuesday night, I finally saw Expiation. Or, as we say in the English-speaking world, Atonement, the 2007 film that starred James McAvoy and Keira Knightley, based on Ian McEwan’s Booker Prize-nominated novel. Yes, the DVD I own of the film was printed for the French Canadian world, hence it’s labelled in both English and French. Everything else about the film, though, is in English. It’s just the label that’s not.

I kind of like that. It makes me feel distinguished, like I have a foreign film in my collection. 😉

I remember seeing the trailer for Atonement in the theater, probably in front of Across the Universe. I was intrigued by the trailer, especially its look and tone, but I didn’t get a good “feel” for the film from it — or what it was supposed to be. I recall seeing the novel in the local Borders that Christmas, and though I was curious I didn’t buy it. After the film came out, I read a few reviews, and while most (like this one from The Guardian) keep the film’s central conceit secret, one I read gave away the entire game — the plot twist in the film’s final fifteen minutes.

I have to admit, though. Knowing the final twist actually made me want to see Atonement more. Only, for whatever reason, I never did. And then, one day, I picked up the Expiation DVD, and it sat unwatched and unloved in my collection until Tuesday.

No, there was no magical reason for watching Expiation… urrr… Atonement on Tuesday.

Atonement begins in 1935.

She naturally draws the conclusion that Robbie is a sex maniac — and interrupting Robbie and Cecelia together in the library only convinces her of that even more.

When Lola’s younger brothers run away during the dinner party, the dinner party venture out into the dark to find them. Briony finds her cousin Lola as she is being raped, and the attacker runs away. Though Briony doesn’t see the attacker clearly — and Lola has no idea who attacked her — she makes a tragic and false accusation, motivated out of misunderstandings, malice, and even jealousy because she is absolutely certain that Robbie is a sex maniac.

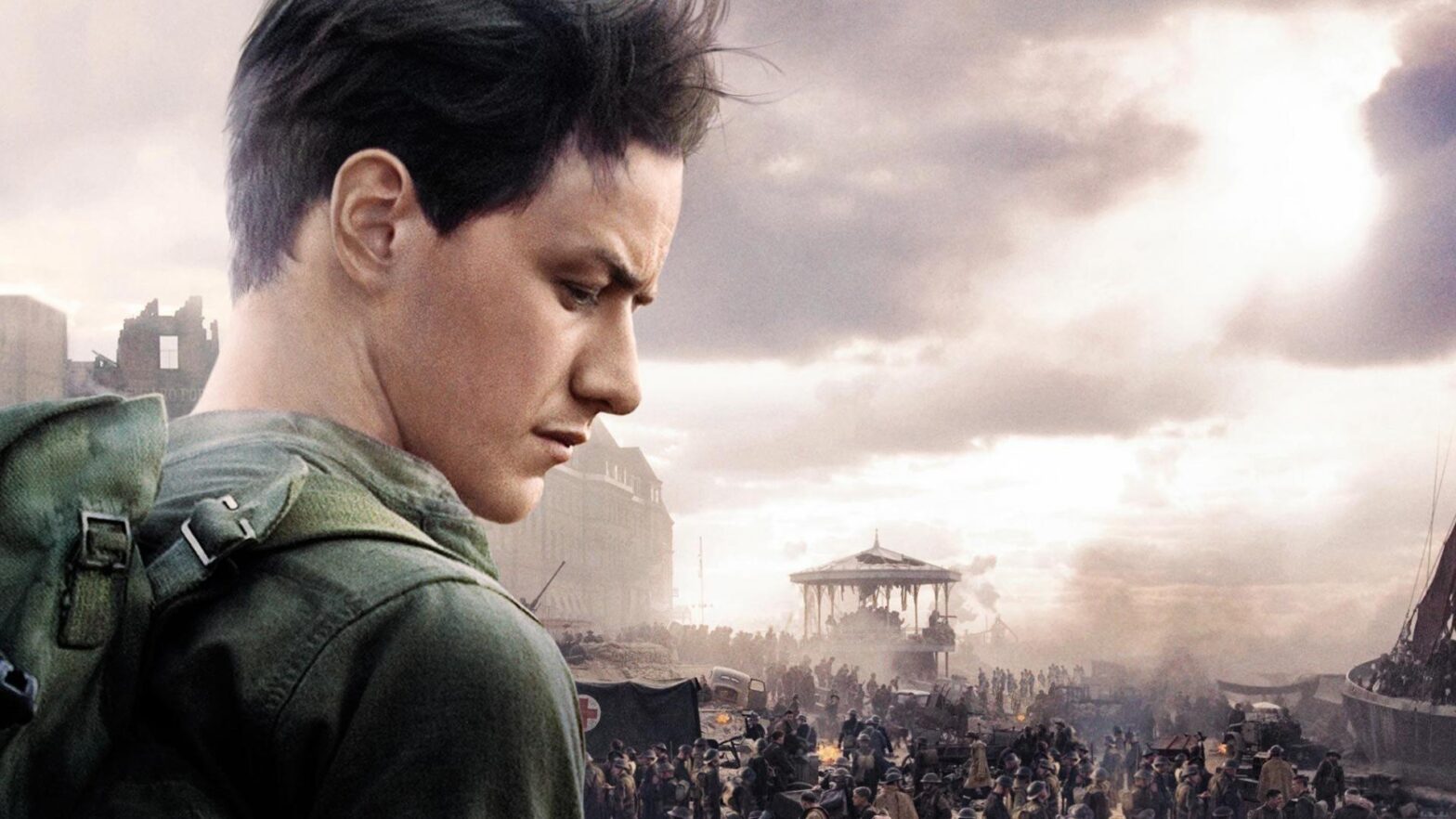

The movie jumps ahead to five years later. Robbie has been released from prison to serve in the British Army, and a long sequence of the film follows his squad’s retreat to Dunkirk. Cecelia walked away from her family after Robbie’s conviction for sexual assault, she works in London as a nurse in a military hospital, and she and Robbie reconnected before his deployment. Briony, now eighteen, walked away from admission to Cambridge to also work as a nurse in a military hospital, and she has begun writing a novel about the events of the night of the dinner party in 1935. She believes, for a moment, that she sees Robbie among the survivors of Dunkirk that have come to her hospital, and this prompts her to find Cecelia, who has had nothing to do with her since 1935, and confess that she knows that her accusation five years earlier was wrong and that she knows who Lola’s real attacker was. She discovers that Robbie is living happily with Cecelia, and after avoiding her for several moments, Robbie confronts her with great vehemence and anger, the pent-up frustrations of a life diverted by her earlier accusation.

Expiation is a beautifully wrought film, only the second from director Joe Wright. (His first was the Keira Knighley Pride and Prejudice.) There’s one single six minute shot at the beach of Dunkirk — no cuts — that captures, quite movingly, the carnage and chaos of the collapse of the British Army. Wright also plays some interesting tricks with time and space in the film; scenes that are implied to take place simultaneously — or at least linearly in relation to one another — are then shown to be other scenes seen from different angles, showing how the characters, especially Briony, are limited in their perceptions and not in full possession of the facts.

I am not ashamed to say that I wept openly at the final ten minutes of the film. I’m reminded of Gandalf’s admonishion at the Grey Havens, “Do not fear to weep, for not all tears are evil,” and Atonement was quite a moving film, and I could clearly understand why it was nominated for seven Academy Awards, including Meilleur Film… errr… Best Picture. The performances, especially James McAvoy as Robbie and Saoirse Ronan and Romola Garai as Briony (aged thirteen and eighteen, respectively), were gripping, and Atonement made me reconsider all the terrible things I’ve said about Keira Knightley’s abilities as an actress over the years.

Yet, the film left me unsatisfied. And the more I’ve thought about it, the more I understand why I feel unsatisfied. The story feels unfinished. The emotional catharsis feels unearned, and I wept not for the story the film told but for the story the film should have shown. Atonement never made me feel that Briony truly atones for her actions in 1935 — nor that she really wants to. For that matter, the film’s ending makes it clear that she cannot.

The film is divided into four “chapters.” The first is the dinner party in 1935. The second is Robbie’s adventures in the British Army in 1940. The third, running parallel to the second (though told after) is Briony’s experiences as a junior nurse in a military hospital in London. The final chapter — the last ten minutes, really, so more of an epilogue — is many years later when Briony, now an elderly and revered novelist, publishes her final book, Atonement, an autobiographical work that covers the first three chapters.

The twist, in the final minutes, is that the ending of the third chapter is wholly fictional.

Briony never went to see her sister to confess that she realized her accusation was false. Briony never saw Robbie in Cecelia’s flat. Cecelia died in the Blitz. Robbie died before he could be evactuated from Dunkirk. They had no happy ending. Yet, Atonement, Briony’s book, gives Robbie and Cecelia the happy ending that she had denied them in life.

This didn’t bother me. Writers tell lies. It’s what we do.

Rather, what bothered me was how the film denied us the opportunity to see the life that Briony had imagined for Cecelia and Robbie. (And I realize this may be a fault of the book, which I have not yet read, rather than the film.) I would have accepted Briony’s feelings of guilt for her actions in 1935 more had we seen the fullness of the lives that Briony dreamed, if we’d had some sense that Briony was living and had lived her life in a way to make up for the lives she had ruined. Instead, Atonement shows us an elderly woman making, essentially, a deathbed confession (the elderly Briony admits that she is dying) of a false accusation of rape that she made sixty-plus years earlier when all the people that it would matter to are dead, gone, and forgotten.

All of that said, Expiation remains a remarkably beautiful film. The performances, especially McAvoy’s, are compelling. The cinematography is nothing short of stunning. It’s just the ending; it sits unwell with me. I don’t mind a film that doesn’t play fair with its narrative, but if a film is going to play unfair then it needs to really embrace the falseness and unfairness of its storytelling.

In other words, Atonement needed to be just a little more like The Sixth Sense. 🙂