“You have been in Afghanistan, I perceive.”

“You have been in Afghanistan, I perceive.”

I first read this line, from the opening chapter of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s A Study in Scarlet, when I was ten. It was the meeting between Sherlock Holmes, soon to be the famous consulting detective, and Dr. John H. Watson, recently invalided home from the front due to injuries sustained in Afghanistan, in the rooms of Bart’s Teaching Hospital, and the lives of the two men would be tied together forever more. They, more perhaps than even Queen Victoria, define the way we, today, look back on the Victorian era. Gaslamps. Fog. Cobbled streets and hansom cabs.

Sherlock Holmes. Dr. Watson.

Every few years, someone pulls Sherlock Holmes off the shelf and takes a crack at the Great Detective — Canada’s Odyssey Network did a series of television films starring Matt Frewer in 2001 and 2002, the BBC did one-off films starring Richard Roxburgh (The Hound of the Baskervilles, 2002) and Rupert Everett (The Case of the Silk Stocking, 2004), and, most recently, the big-budget film Sherlock Holmes starring Robert Downey, Jr. (as Holmes) and Jude Law (as Watson) from director Guy Ritchie.

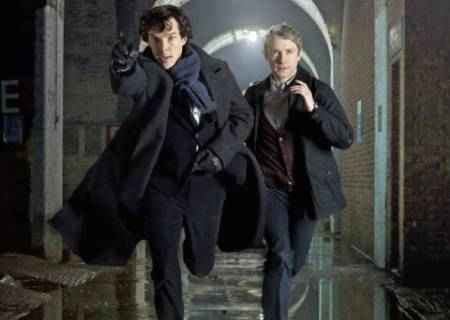

Last week, BBC1 debuted a new series, Sherlock from Steven Moffat of Doctor Who and Mark Gatiss of The League of Gentlemen. (Full disclosure: I have been compared favorably as a writer to Moffat, and Gatiss called me an “anal-retentive asshole” a decade ago. I shall endeavor to be fair in light of both.) Rather than produce a period piece, set in the Victorian milieu as these other recent productions had, Moffat and Gatiss decided to make a Sherlock Holmes that is contemporary, who lives in a world of cell phones and automobiles, of Google and modern techonology. Said Moffat: “Conan Doyle’s stories were never about frock coats and gas light; they’re about brilliant detection, dreadful villains and blood-curdling crimes — and frankly, to hell with the crinoline. Other detectives have cases, Sherlock Holmes has adventures, and that’s what matters.” And for three weeks, we get Benedict Cumberbatch (and what a fantastically English name that is!) as Holmes and Martin Freeman (best known for his role in The Office or as Arthur Dent in The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy film) as Watson.

I will be honest. I was wary of a “contemporary” Holmes. When I think of Holmes, I think of the Victorian milieu. I want the cobblestones, I want the gaslights, I want the hansom cabs and the Meerschaum pipe and the deerstalker. A contemporary setting for Holmes makes me think back on the Arthur Wontner films of the 1930s or the Basil Rathbone films of the 1940s, where Holmes was brought into the present day and Moriarty was in league with Nazi spy rings. But then again, I’ve enjoyed unconventional takes on Holmes; just last week, I reread Neil Gaiman’s “A Study in Emerald,” his Hugo Award-winning Sherlock Holmes story based on A Study in Scarlet set in a world where Lovecraft’s Elder Gods conquered and dominated humanity in the Middle Ages. (This story can be found, by the way, in Michael Reeves’ Shadows Over Baker Street, a Holmes/Mythos collection, or John Joseph Adams’ The Improbable Adventures of Sherlock Holmes.)

The first episode, “A Study in Pink,” written by Moffat, aired last week in the UK (and will air in October on PBS as part of Masterpiece Mystery). Loosely based — stress on the “loosely” — upon A Study in Scarlet, John Watson has returned to Britain due to wounds sustained in the Afghanistan War. Needing for a flatshare because he cannot live in London — “and wouldn’t want to live anywhere else” — on an Army pension, he is introduced to a strange man at Bart’s by his former Med School classmate Stamford. This odd man makes a series of observations about John, from his military service to his family situation, that prove unnerving — and unnervingly accurate. Soon, John is checking out an apartment at 221B Baker Street with Sherlock Holmes, and the great literary partnership is born in a new age.

But all is not well. Over the past few months, Scotland Yard has been investigating a series of suicides that are all eerily similar. Some in the press question if there might be a serial killer at work, while Detective-Inspector Lestrade stresses that all available evidence is that, no, these are suicides. But soon, Lestrade arrives at Baker Street — there is a new suicide in a rundown building in Lauretson Gardens that fits the profile, only this one left a note.  Soon, Sherlock and John are on the hunt for the piece that will link these suicides together, and the meaning of the word “Rache” that the latest victim scratched into the floor.

Soon, Sherlock and John are on the hunt for the piece that will link these suicides together, and the meaning of the word “Rache” that the latest victim scratched into the floor.

How was it?

I hesitate to call Sherlock: A Study in Pink superlative, and yet that’s the word that best fits. It really is superlative. Moffat’s writing sparkles, from the sharp dialogue (the line “I’m not a psychopath. I’m a high-funtioning sociopath” is particularly good) to the way the writing brings us inside the mind of that high-functioning sociopath and how he sees the world. (It is reminiscent of the scene on the Leadworth green in Doctor Who‘s “The Eleventh Hour,” by the way.) Cumberbatch has the manic energy and the histrionics of Doyle’s Holmes, he clearly sees the world as a game, and his performance is pitched somewhere near Jeremy Brett’s classic portrayal in the long-running Granada television series of twenty years ago or Robert Downey, Jr.’s, but without the ennui that these Holmes evidenced on occasion. The real star of the episode, though, was Freeman; he’s the everyman, he’s not an idiot, he has his own views, and he comes across as the rock in this world. The direction, too, was good; Paul McGuigan’s camera work was solid, and some shots (like a panning crane shot outside 221B Baker Street) evoked memories of similar camera work in the Jeremy Brett series. (Also, I would swear that one of the suicide victims lived on The Sarah Jane Adventures‘s Bannerman Road.)

As an amateur Holmesian, I cheered at some some lovely Canonical touches in “A Study in Pink.” One of the suicide victims was James Phillimore (“who, stepping back into his own house to get his umbrella, was never more seen in this world,” mentioned in “The Problem of Thor Bridge” in The Casebook of Sherlock Holmes). The sitting room at 221B was suitably disheveled, affixed to the mantelpiece was a knife (where Holmes kept his correspondence), and while a patriotic “VR” above the fireplace made with bulletholes is unlikely there was a Union Jack throw pillow. The “three-pipe problem” becomes a “three-patch problem” as in “nicotine patches.”

Despite being the first story in the Holmes canon, A Study in Scarlet is not often adapted, perhaps because it’s not much of a Sherlock Holmes story and he does very little in the course of the novel; the bulk of the book is a story of the Mormons and their migration across the North American continent, which ultimately leads to a sordid tale of revenge in London. Sadly (or maybe fortunately, because that part of the book has always bored me stupid), there were no Mormons in “A Study in Pink,” and if the murderer’s name was Jefferson Hope I never heard it. I would say, come to think of it, that the murderer was the weakest part of the episode. Besides the fact that I’d worked out who the perpetrator was likely to be (although we had not met him by that point) long before Holmes did, his motives made little sense — and I’m not sure that his scheme would really work. Still, the sharpness of the writing overall — and the tension of the final confrontation — make up for that failing. As Steven Moffat rightly notes, the thrill of Holmes is in the adventure, not the case. It’s the chase that matters.

The BBC is happy with the ratings for the first episode — 7.5 million, roughly what Doctor Who was drawing in the just-finished season — and they’re contemplating a second. I hope so, I liked this take on Sherlock Holmes. And hopefully the writing and acting for “The Blind Banker” and “The Great Game” stay as strong as they were in “A Study in Pink.” Sherlock could very well be a Sherlock Holmes for the ages.

I’ve seen ‘A Study in Pink’ since I first read this, and liked it too; I’ve also seen the second but not the third one. The murderer’s name may not have been Jefferson Hope (or it may; I don’t think it comes out), but

s

p

o

i

l

e

r

s

p

a

c

e

he was a cab driver.

I still have to watch the second and third episodes; they’re waiting for me, the moment I have the time. This weekend, hopefully. 🙂