In 2012, I took a vacation. A brief one, just two days. I went to New York City to see the Lewis Chessmen. (Due to some poor planning on my part, I did not see them then; I had to go back over the weekend. Story of my life.) That was, sadly, my last vacation from Diamond. I could take a day here and there, but stringing together multiple days in a row with the deadlines and the company’s shorthandedness and, in 2017, taking a paycheck hit due to the way the company handled the Obama administration’s new overtime rules? Time off didn’t happen.

This year, there was a brief window where I might actually be able to get away from the office, and when it coincided with my niece’s piano recital in North Carolina, I saw an opportunity to get away for a few days. A whole week was impossible, but there was some potential, and I started making some plans. Are there baseball games I can go to? I started looking at schedules for minor league teams and college teams. My grandmother’s side of the family comes from the Rocky Mount, North Carolina area. Could I figure out where her ancestors were buried so I could visit and take pictures? A schedule formed, and early Friday morning, hours before dawn, I set out for North Carolina, stopping for breakfast at Aunt Sarah’s Pancake House in Richmond.

South of Petersburg it began to drizzle. By early afternoon I was in Rocky Mount, heading east into Edgecombe County, driving down some back roads, looking for two private family cemeteries where my grandmother’s parents and grandparents were buried. I had scoped out the area on Google Maps and didn’t see anything that looked like a cemetery, small and private or otherwise. I didn’t know exactly what I was looking for or what it would look like, but when I saw it, on my right, I knew I’d found it — two headstones rising from a field. I pulled off the road in the middle of farm land, briefly wondered if I needed to ask someone (who?) for permission for what I was about to do, and walked across a field.

In the midst of this field of something that had begun to sprout in the North Carolina spring — I’m no farmer, and couldn’t tell you what anything is — there was a small cemetery, enclosed by a fence. What I saw from the road was two tall pillars, and as I approached on foot I could see that there was a third, much smaller headstone there, for someone I never knew existed, someone who never even had a name — my grandmother’s brother, who was born and died the same day.

I struggled with the gate, contemplated simply scaling the fence, decided against that because I’m not as young as I used to be, and eventually got the gate open enough so that I could squeeze through.

Then I stood where my great-grandparents — Joseph and Mattie (Williford) Lancaster — and great-uncle were buried.

It was well-maintained. I think I expected to find something overgrown, and it was nothing of the sort. The ground was a little spongy, but not alarmingly so.

I was intrigued by the footstones. Not only were there the pillar monuments, but there were little footstones with their initials carved. I’d not seen anything like this before.

The headstones were remarkable. They were beautifully carved and had aged quite well. They were also very tactile; the surface felt “gritty” (similar to the way the monument where my great-great-grandmother Susan is buried feels) but it felt natural, like it was due to the way the stone was carved, not because of time and weather.

My mother told me that this land is where my great-grandfather’s farm was. She also told me that the last time she visited the cemetery plot, she would have been about fifteen or sixteen. “It was the only time I can remember your grandmother wanting to go,” she said, “and she cried and wailed” when my grandmother went to the grave of her dead mother. My mother didn’t even go to the funeral when her grandfather was buried here; he died a month before I was born, and her doctor recommended she not attend to prevent a premature birth.

I put my hand on the ground where my great-grandparents are, and I stood for a little while and looked at the infant. My grandmother would have been almost ten years old when he was born and died. She carried a lot of pain in her life; was this another piece of her pain? Did she spend several months thinking about the brother or sister she would have, only to then see that brother go into the ground a few days after he was born?

I took a few more photos — best to have too many that too few — before I refastened the latch and walked back to my Beetle.

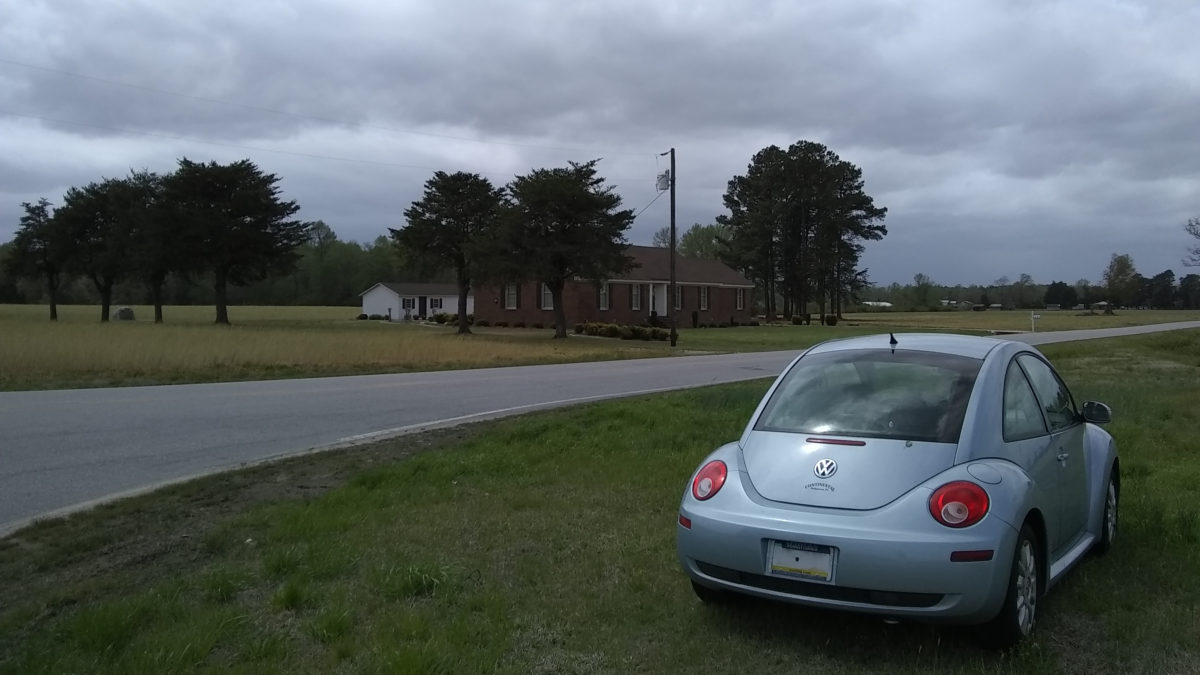

The next cemetery that I was looking for was the cemetery where Joseph Lancaster’s parents, William and Mary Ann (Williams) Lancaster, were buried. The directions I had suggested it was about a half mile south and much further back from the road. Once I was back on the road, though, I saw it almost right away. Yes, it’s a little further back, but not by much, and it’s only about a quarter of a mile away, not a half.

It was also in someone’s back yard.

I parked the Beetle across the street, walked up the driveway, and, having seen two cars behind the house, knocked on the door. I waited. No answer. I knocked again, waited again, no answer again. I shrugged, walked around back, noticed briefly that the back door was open through the storm door (suggesting that someone was, in fact, at home), and walked straight toward the cemetery.

The first thing to notice was that this cemetery was in the middle of plowed fields; three of its four sides were bounded by fields that had been tilled, may have already been planted, and would in summer be verdant and green. I tread carefully.

I was not as well versed in the history of this branch of the family tree, and I didn’t know what I would find. Great-great-grandparents, that I expected. I also found three great-great-great-grandparents. That I did not expect.

In some respects, the least interesting of the stones were those belonging to William and Elizabeth. They were quite plain, they had not aged well, William’s had broken and been cemented back together, and Elizabeth’s was askew (as you can see by how I rotated it below) and in serious danger of being overgrown by that tree.

There was a rather unique headstone for the first person buried here, Elizabeth’s sister Sally Ann. I have no idea if this is the original or a reproduction made, but either way, it was unique enough to note.

There were many Williams here, including Elizabeth’s parents, James and Mary Ann Williams. And here I found the thing I really didn’t want to find — I have a Civil War veteran as an ancestor, and one on the rebel side, at that. I have World War II ancestors. I have War of 1812 ancestors and Revolutionary War ancestors. I had not been able to find a Civil War ancestor, on either side. And here one was, staring me in the face.

These headstones were quite impressive, similar in style to Joseph Lancaster’s headstones — same type of stone, same carving style, same script, same tactile feel, same aging — even though they are many, many years older. The only questionable detail, from my 21st-century multicultural viewpoint, is the statue of a Confederate soldier at the base of James Williams’ statue. He was, as best I’ve been able to determine, a private in the 17th North Carolina Infantry Regiment (2nd Organization), even though he was already into his late thirties at the time the war began.

The truly unexpected find was William Lancaster’s mother, Sarah (Howell) Lancaster. I do not know if her husband (and my great-great-great-grandfather) Levi Land Lancaster is here or elsewhere. I looked at everything, and saw nothing. There are other Lancasters marked here, but Levi is not among them.

My family has been here for a long, long time. My Lancaster line goes back to Robert Lancaster or Lanquishear, who was in Virginia before the Restoration.

The cemetery was an active one; there was a burial from 2017 that hadn’t yet begun to grow grass again. I took a few more pictures, then walked back to the Beetle, skirting the edge of the field between the cemetery and the road, trying to stay as far from the house as I could. I’d already intruded upon their space enough. No need to compound it by walking back along their driveway.

On my way to Raleigh, it began to drizzle again, and there would be brief cloudbursts of heavy, intense rain that lasted no more than a minute or two. A typical North Carolina April, then. It was so lush and green. I’d forgotten how much I loved driving on North Carolina’s roads.

I’d seen what I’d come to find, and a bit more. I don’t know that I will ever be back that way. It was a good excursion.