On April 14, 2018 I went to Cecil County and explored four cemeteries, looking for graves I knew about and graves I didn’t. I had been planning this for about two months, and you never know what you’ll find until you go and look.

The roots of my dad’s family come from what I jokingly call “the borderlands between Maryland and Pennsylvania” — ie., Cecil and Chester Counties — as ancestors, Gibsons and Browns, Reynolds and Russells, go back and forth across the Mason-Dixon Line for two hundred years. Some lore indicates family arrived in Cecil County from Scotland after the War of 1812 or before the American Revolution, other records indicate early settlers of Pennsylvania that moved westward and southward. The truth is that I don’t know a lot about my ancestors, which is why researching my ancestry is so fascinating.

As an historical aside, the border between the two colonies wasn’t a joking matter; the land grants overlapped, Maryland’s charter granted it lands to north of modern day Philadelphia, Pennsylvania’s charter granted it lands to the northern end of the Chesapeake, and the two colonies fought a strange border war known as Cresap’s War or the Conjocular War, until it was finally resolved by the drawing of the Mason-Dixon Line.

Ebenezer United Methodist Church in Rising Sun was the first of the four cemeteries I visited. This is where my great-great-grandparents, Alexander and Albina (Brown) Gibson, are buried. Alexander’s middle name was Craig. Based on headstones at Principio Methodist in Perryville, I have begun to wonder if Craig may be a family name of one of his ancestors.

Also buried at Ebenezer are William and Lydia Mary (Hambleton or Hamilton) Gibson and six of their children. William was Alexander’s younger brother. Their parents, Hugh and Mary Eliza (Gillespie) Gibson, had a number of children; of them, I think my favorite name is that of their daughter Minerva, named presumably after the Roman goddess of strategy and tactics. William and Mary (she apparently went by her middle name) had seventeen children. Two of the children (one of them buried here) were twins, so Mary was pregnant sixteen times. That’s twelve years of her life, pregnant. That’s a staggering amount of time, seventeen percent of her life.

Not all of William and Mary’s children died in childhood, and two of them that reached adulthood are also buried here, their daughter Wilhelmina and their son James. While I was unable to locate Wilhelmina’s grave, James and his family have prominent markers along Ebenezer Church Road.

I was struck by how small the church cemetery plot was. I didn’t know what I expected. To the south side of the church, where my great-great-grandparents are, the headstones were older. Some were worn away and almost unreadable. To the north, the headstones were much newer, and most were from the last forty years or so.

For more photos from Ebenezer, check out my Facebook photo album: Cemetery Explorations in Cecil County: Ebenezer.

The second cemtery I visited was at Hopewell United Methodist Church in Port Deposit. My grandfather and his parents are buried here, as well as brothers and sisters and nieces and nephews of my great-grandfather.

Of the four cemeteries I visited, Hopewell was the largest. It was also the only one of the four for which I had a map before arriving, though the map was heavily stylized and did not conform at all to the geography on the ground. At least, though, it marked out the sections; I had locations for people, and without those and the map I could have wandered all day. Hopewell was old as the age, styling, and weathering of headstones would attest, but it was also an active cemetery in that there were fresh graves and graves from last year that had not yet regrown grass.

My great-grandparents Edward and Olive (Russell) Gibson.

Edward was a farmer. That’s really all I know of him. I’ve seen a photograph of him, and to some extent he resembles my father, though with more hair. Olive was an orphan. She lived with her uncle, David Harding, and his wife in Oxford, Pennsylvania. Unraveling Olive’s parentage took me a while. Her mother Amelia was David’s sister, and the Hardings appear to have come from the Fair Hill, Maryland area. Her father was Alexander Russell. My dad tells me that Olive had brothers, and they were split up among the family. One of the brothers took the last name Harding, and he says that Olive herself was known by some of the older residents of Rising Sun as “Grandma Harding.”

At the foot of their graves is a stone, flush with the ground, for my grandfather, David Gibson. He was cremated, and his ashes were interred at his parents’ feet. I can’t say that I really knew him. I spent time with him over the years. I received birthday cards from him. He paid us visits here and there, such as the time he came to visit in December before Christmas unexpectedly, stayed for a week, and departed one day.

I managed to find everyone at Hopewell that I went in search of, including, surprisingly, the grandparents of a friend of mine who has an obscure last name. (I noticed the name in the cemetery records, sent him an email and asked, “By any chance…?”, and it turned out that was his grandparents.) I could see, as I walked the grounds, the way the cemetery had developed. The oldest graves were, of course, the ones closest to the church, and looking at the way the headstone styles changed I could see that the cemetery expanded in one direction, out toward the woods behind the church, and then grew in another direction, along the road. There were more elaborate stones here than at the others; there were obelisks and crypts, long elevated slabs and marble blocks, even two mausoleums. I could have spent more time here, but I had a schedule to keep.

For more photos from Hopewell, check out my Facebook photo album: Cemetery Explorations in Cecil County: Hopewell.

Principio United Methodist Church in Perryville was my third cemetery to visit. My grandmother Helen (Brown) Gibson, and her parents, Charles Benjamin Harrison Brown and Ethel Matilda (Reynolds) Brown are buried here.

My grandmother, “Mom Mom,” died when I was four. The only memory I have of her is a vague one. I remember a house (a shack?) somewhere near the water. I remember sunlight and reeds and a gravel road and the bay. I remember a book of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs that was illustrated and seemed to be very old. I’d never been to visit her, even when I lived in Chester County fifteen years ago. I felt like I should have said something profound. Instead, all I said was, “I kinda remember you.”

Charles Brown’s family came from Pennsylvania; his parents are buried in Little Britain in Lancaster County. I’ve seen a photograph of Charles when he was a child (late 1890s), with his siblings and parents outside of what I would presume was their farmhouse. His parents were obviously Republicans; in addition to Charles’ wonderfully 19th-century double middle name after the president at the time he was born, he had a younger brother named Theodore Roosevelt Brown. As I understand it, he was struck and killed by a train. Of my great-grandmother Ethel, I know nothing beyond her parents.

My great-great-grandfather whom I visited at Ebenezer was named Alexander Craig Gibson. His father was named Hugh Boyd Gibson. His location is unknown. (I know of a Hugh Boyd Gibson buried in Havre de Grace, but that’s a grandson though Hugh’s son James.) I had made the assumption that “Craig” and “Boyd” were simply middle names of little to no import. I could not tell you, for instance, why my great-grandfather Allyn Gardner had the middle name of “Atworth”; it seems quite random to me, and the people who made that decision have both been dead for well over a century. Graves at Principio are making me reconsider my working assumptions, as there are a number of Craigs and Boyds buried here, especially in this old section closest to the rear of the church. The row of headstones in the middle is a row of Craigs. “Craig” may indicate that there was a Craig in Alexander’s ancestry. “Boyd” may likewise indicate the same for Hugh.

I was also intrigued by the carvings on some of the old headstones. A number had what looked to be a carved willow tree that towered over a coffin? a grave? I wasn’t really sure. (Examples in this photo are center right, Victor Craig and his son Victor.) I found headstones of the same style at Hopewell, and they were among the oldest graves and the ones closest to the church there.

There are also a number of Gillespies here, and Hugh Gibson’s wife was a Gillespie, Mary Eliza (or Elizabeth) Gillespie.

This is Hugh Boyd and his wife Margaret. I wasn’t sure where their graves actually were, as their headstones were leaning against the headstone for J. Henry Boyd. Hugh Boyd was born either August 31 or September 1, 1785 — I love headstones that require one to use math — and Margaret was born December 26, 1802 and died sometime in 1862 or 1863. J. Henry could possibly be their child, but as he was born in 1848, Margaret would have been 44 or 45 when he was conceived and at the upper limit of her childbearing years. Relatives of Hugh Boyd Gibson? There are plausible scenarios I can construct in my mind, cousin or uncle, too young to be a grandfather, but I have no idea. The coincidence of names can easily lead one to see patterns in the chaos where there are none.

There are also two Gibsons here, William Gibson (1815-1859) and his wife, Ellen (1823-1898), but I have no idea if they are relatives or not. I know nothing of Hugh Boyd Gibson’s ancestry — parents, siblings, anything — and William T. Gibson would be a few years older than Hugh Boyd Gibson.

For more photos from Principio, check out my Facebook photo album: Cemetery Explorations in Cecil County: Principio.

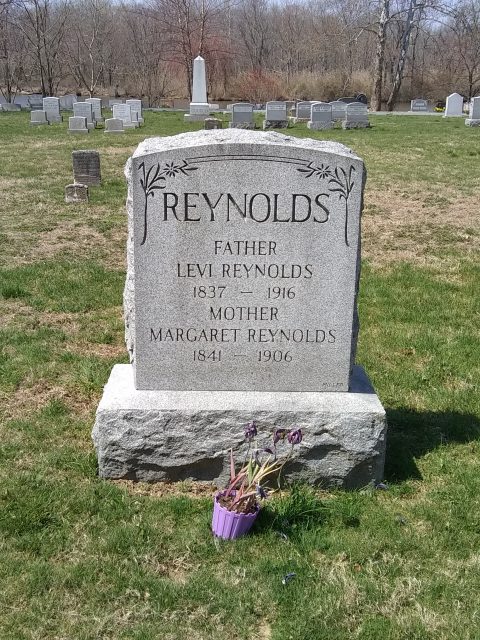

The last cemetery on my itinerary, the fourth, was North East’s St. Mary Anne’s Episcopal. Ethel Matilda (Reynolds) Brown’s parents are buried here, William and Alfonsa (Howell) Reynolds, as well as William’s parents, Levi and Margaret (Reynolds) Reynolds.

Of the four cemeteries I visited, St. Mary Anne’s was both the oldest and the loveliest. Oldest, because some of the headstones dated back to the 1730s. Loveliest, because the cemetery backed up against the North East River, and as I wandered the grounds on this lovely spring day it was quite serene and peaceful.

The grave of my great-great-great-grandparents Levi and Margaret Reynolds.

The grave of my great-great-great-grandparents Levi and Margaret Reynolds.

Levi originally came from Virginia (according to his death certificate), but his parentage in unclear. He moved to Pennsylvania before the Civil War, and married Margaret in Oxford, Pennsylvania in 1860. After the war, he and his family relocated to North East and he worked for the McCullough Iron Company.

This grave was remarkably easy to find. One need only walk between the chapel and the vestry house behind it, then turn to the left and there, standing quite tall and prominently, is their headstone.

To my eyes, it looks to be far more recent than early-20th-century. I suspect this is not the original headstone. It looks far too modern.

I have no idea who left Levi and Margaret flowers recently.

Their son and my great-great-grandfather, William Reynolds, and his wife, Alfonsa (Howell), are also buried here at St. Mary Anne’s, but they appear not to be marked.

To the left of the Reynolds headstone is a simple slab headstone with the initials “J.A.R.” carved into it. To the right is a ground-level slab for Robert Reynolds, the son of Levi and Margaret, who was a mailman in the area. I suspect that William and Alfonsa are probably nearby.

Near the Reynolds’ grave was a grave adorned with the Stars and Bars. This belongs to Private James Lowndes.

St. Mary Anne’s had some truly old graves. Behind the vestry house, near the Reyonds headstone, were rows of graves that were nothing more than slabs of rock. Some had initials or dates chiseled into them. Most did not.

Some headstones dated back to the 1730s. These two have been obliterated by time. The one clear date is on the stone to the right; all I can make out is “Deyed March 12 1734.” The headstone to the left may have a date on it of “1737” at the bottom. Or it may not.

The carving on the oldest headstones, those from the 18th- and early 19th-centuries, featured antiquated script and spellings, such as “Aprile” instead of “April,” the superscript “t” as a suffix in place of “-ed,” and the long S (which, to modern eyes, looks like an f without the crossbar). Wandering the grounds, I could feel the history there, and I couldn’t help but put my phone to the chapel’s windows to snap a few pictures of the interior.

I wouldn’t have expected to see a pre-1801 Union Jack (a version without the St. David’s Cross representing Ireland), but the little of the history of the church that I know gives it some sense. There is no “St. Mary Anne.” The parish was originally named St. Mary’s, and when Queen Anne died she bequeathed the church a bible, a Book of Common Prayer, and a silver chalice set. In her honor, her name was added to the church’s name, hence, St. Mary Anne’s, and a Union Jack in her honor makes sense.

For more photos from St. Mary Anne’s, check out my Facebook photo album: Cemetery Explorations in Cecil County: St. Mary Anne’s Episcopal.

When I made my plans, I could not have chosen a better day to explore cemeteries.

In some ways, everything that followed was anti-climax.

I went to Cecil Con, a comic book and media convention at Cecil College. For what it was, it was fine.

I capped my day of exploring cemeteries in Cecil County with a baseball game in Wilmington, Delaware. I don’t know how many times I’ve been past Daniel S. Frawley Stadium on I-95, but I’d never been to a game there, and since I was in the area and it was a nice day it seemed like a good thing to do.

The Wilmington Blue Rocks played the Lynchburg Hillcats. The Hillcats were winning… and then they lost.

Like pretty much every Carolina League baseball stadium I’ve been to, the outfield wall is nothing but advertisements. However, the ads at Frawley weren’t too overwhelming (a real problem in Frederick, imho), and the upper row was actually set back from the outfield wall. Plus, the outfield wall didn’t cut the stadium off from the world outside; from the third base side downtown Wilmington was visible, and from the first base side Amtrak trains and traffic on I-95 zipped by.

I could see why the Binghamton Mets considered relocating to Wilmington a few years ago. (The plan would have sent the Blue Rocks, a High-A team in the Carolina League to Kinston, North Carolina, with the AA Mets taking their place in Wilmington’s stadium.) The stadium was spacious and could seat at least 6,000, if not 7,000. Certainly it was the nicest, or second nicest, Carolina League stadium I had ever visited.

The Star-Spangled Banner was performed by the Downingtown Area School District Fifth and Sixth Grade Band. (I drove through Downington every day to go to work at EB Games in Exton fifteen years ago.) The kids were not allowed to take their instrument cases into the stadium, though, a fact the parents I passed on my way into the stadium were grumbling about as they took the cases back to their cars in the lot.

Overall, it was a nice evening for a baseball game, especially once the sun went down beyond the third base bleachers.

Wilmington’s crowd was enthusiastic. Sometimes I can go to a minor league game and feel like the baseball is the least important thing happening there. I thought here it really was about the game, and the crowd went wild when the Blue Rocks finally solved the puzzle of Lynchburg pitching, clawed their way back, and took the lead and the victory.

Wilmington’s crowd was enthusiastic. Sometimes I can go to a minor league game and feel like the baseball is the least important thing happening there. I thought here it really was about the game, and the crowd went wild when the Blue Rocks finally solved the puzzle of Lynchburg pitching, clawed their way back, and took the lead and the victory.

All in all, the Cecil County outing was a success. I explored four cemeteries and found some things, like Hugh Boyd and the Craigs at Principio, that may be fruitful. I visited ancestors who were really just names on paper and stood in places where people who had known them and loved them once stood. I visited churches where history happened and marveled at the artistry of carvings done two hundred and fifty years ago. I felt the weight of years, and marveled in the serenity of a spring’s day at the shores of North East River. It was a good outing, a necessary outing, and I felt like myself.

I was searching for burial places of Gibsons and stumbled on your good work. Thank you so much; my wife and I are planning a visit to the Cecil County area this June and will visit the Gibson sites.

From ancestry, your theory about the Craigs is correct as Mary Gillespie’s mother is Elizabeth Craig. The Craigs are an old and extensive family in Cecil County.

As for the Hugh Boyd Gibson mystery, I’m sure he is similarly tied to the Boyds, Who have at least 3 generations of Hughs., but I haven’t been able to find the missing link.

There are at least three generations of Hugh Boyds, also at least three of Hugh Gibsons. Somewhere there must be a link. Hugh Gibson didn’t drop down from the sky from nowhere. I have enclosed two stories retrieved from ancestry which might be interesting, if not pertinent. I have constructed family trees for Gibson , Boyd, Gillespie, and Craig, as well.

5/9/2018 Gibson’s Immigrate to USA

https://www.ancestry.com/mediaui-viewer/tree/9182186/person/6572603152/media/153280f8-d754-4986-b7cb-b6ea4499635d?_phsrc=cco22480&_phstart=successS

Researched and written by Jimmy Locke Robert Gibson, or as some sources claim, David Gibson, was born 8 February 1699 at Six Miles Creek, Stewartstown, County Tyrone, Ulster Province, Ireland. H e married Mary McClelland about 1720 in Ireland. Mary was born about 1700 in County Donegal, Ulster Province, Ireland. Ulster, one of the four traditional “kingdoms” of Ireland, was only 20 miles across the channel from Scotland. Under an agreement with King James of E ngland, the lands “should be planted with British Protestants and that no grant of fee farm should be made to any person of mere Irish extraction.” So back in S cotland, with an ever increasing hardship due to the spread of a form of land tenure, called the feu, which had the eect of dispossessing many farmers of their traditional lands, a large migration of Scots travelled the channel to take advantage of the economic advantages of Ireland. However along with this migration came religious turmoil. Under the Jesuits the Irish people had become fervently Catholic and viewed the Protestants of Ulster as heretics and interlopers. A round the year 1717 the first of five large migrations to the Americas began. The first was touched o by a combination of a five-year drought, rack-renting, which means excessive taxation on our land and homes, a diminished trade in woolen goods, financial depression and religious discrimination and persecution. There were but two real drawbacks to coming to the Americas – the perils of an ocean crossing and the expense of passage. A long the time of the third migration, Robert and Mary came to the Americas in the year of our Lord 1740 along with their five children; Robert,18; Andrew, 16; John, 14; Israel, 12; and Mary, age 8. They settled on a plantation of their purchase in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, two and a half miles below Peach Bottom Ferry, on the Susquehannah River. There, their sixth child, Hugh, was born. “ Like all Scotch-Irishman the Gibsons did things – great things – and followed the Dutch maxim of “Sage nicht und sie still” – say nothing and be quiet. In this they were unlike their “down east” Puritan neighbors who when they accomplished anything great or small told the world of it as a hen cackles about her newly laid egg, and those Puritans have been cackling ever since they stumbled onto Plymouth Rock. Scotch-Irishmen did great things and did them as part of their allotted work, and had nothing to say about them. R obert died 13 March 1754, at the age of 55, in Derry, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania. Aer Robert’s death, Mary is oen noted as the “Widow Gibson.” She and her family move to a place in the vicinity of Robinson’s Fort, nearly twenty miles from Carlisle, and at length, in consequence of danger from Indians, moved in 1756 into the Fort. On 1 July 1756, at the age of 56, Mary was killed in a brutal attack by Indians at Shermans Creek, Perry County, Pennsylvania.

Content proveided by Hugh Gibson Hugh Gibson, the son of Robert Gibson and Mary McClellan, was born in February of 1741 near Peach Bottom Ferry in Lancaster Co, Pennsylvania. While he was still young, his mother in her widowed state, along with his brother, Israel, and sister, Mary, moved in the vicinity of Robinson’s Fort, nearly twenty miles from Carlisle, and at length in consequence of danger from Indian attacks, moved along with other neighbors into the Fort in 1756. The Indians had murdered some persons in the Shearman’s Valley in July and waylaid the fort in harvest time, and then kept quiet until the reapers were gone. When they thought things had quieted down, James Wilson and Robert Robinson were out hunting deer, for the use of the company. Wilson while standing at the Fort gate desired liberty to shoot his gun at a mark, upon which he gave Robert the gun which he shot. The Indians on the upper side of the fort, thinking they were discovered, rushed on a daughter of Robert Miller and instantly killed her and shot at John Simmeson. They then made the best of it that they could and killed the wife of James Wilson. While the Indian was scalping Mrs. Wilson, Robert took a shot at him, wounding him, but he escaped. About forty of the Fort’s inhabitants were out reaping in the field when that attack occurred. W hat follows is an interview with Hugh Gibson that was recorded by Archibald Loudon, the first historian from Perry County territory, in his book, Loudon’s Narratives. Remember, Hugh was only fourteen years old when this occurred. O n a certain morning in the latter part of July, me and my mother, with Elizabeth Henry, went out in search of our cattle. We were unexpectedly beset by a party of Indians. My mother was shot at some distance from me, and Sarah Wilson, who had joined her, was tomahawked. I heard the gun, which had proved instantly fatal to my mother, and was immediately aer pursued by three Indians, from whom I attempted to escape; but soon finding it impossible to outrun them, stopped, and entreated them not to take my life. One of them had already aimed his rifle at me, but the powder merely flashing in the pan, the contents of the deadly weapon were not discharged. I was taken by one of the Indians, who was a son of King Beaver, and was aerwards presented by him to Bisquittam, another Delaware chief, and an uncle of the captor. Elizabeth Henry was also captured at the same time. The party of Indians, to whom the three above-mentioned belonged, consisting of about twenty, had killed a number of hogs two or three miles o, and, having breakfasted upon the swine’s flesh, took their two young captives through the trackless desert over the mountains, to Kittanning on the A lleghany river, now the site of the pleasant village of Armstrong. From this place I and two Indians rode to Fort du Quesne, standing near the extremity of the point of land formed by the junction of the Alleghany and the Monongahela, about sixty miles from Kittanning. Here I was first introduced to the before-named Bisquittam. Elizabeth Henry was conducted to some distant region, and I never saw her again. Bisquittam was one of seven brethren, all high in authority among the Delawares of the West. One of these had been killed by the Cherokees, and I was adopted, according to aboriginal usage, to supply his place in the royal family and of course ever aer, while residing with his savage associates, bore his name, which was Mun-hut’-ta-kis-wil-lux-is-sh’-pon,— a compound long enough for the cognomen of an eastern prince, yet of somewhat an uncourtly signification, as it is, literally interpreted—Big-rope-gut-hominy. A t the first interview, Bisquittam, addressing himself to me, said, “I am your brother,” and, pointing to one aer another in the company, added, “This is your brother, that is your brother, this is your cousin, that is your cousin, and all these are your friends.” He then painted me and told me that the Indians would take me to the river, wash away all my white blood, and make me an Indian. They accordingly took me to the river, plunged me into the’ water, thoroughly washed me from head to foot, and conducted me back to his master and brother. He was then furnished, in Indian style, with a breech-cloth, leggins, capo, porcupine moccasins, and a shirt. Aer this ceremony I returned with my new friends to Kittanning. I was at the Middle Kittaning at the time the Upper Kittaning was destroyed by Colonel Armstrong, and heard the deadly firing. As the Indians were about to pass over to the east side of the river and to the scene of carnage, I asked Bisquittam what I should do. He said, “Go to the squaws, and keep with them;” which I did. At that encounter, well known in Indian warfare, Armstrong lost forty men, and the enemy but fourteen, as reported by the Indians. Captain Jacobs, a noted warrior in those days of terror, killed, while under the covert of the house in which he was posted (his squaw assisting him in loading his guns), no less than fourteen, and refused to surrender, though repeatedly urged. At length some of Armstrong’s men threatened to burn the house over his head. He replied, that they might if they would; he could eat fire.” He and his wife were burnt with the house. In the contest Jacobs had received seven balls before he was brought upon his knees. At this time, besides Jacobs, his brother and another great warrior were among the slain. The Indians told me that they had rather have lost a hundred of their men than those three chiefs. I was now compelled to witness a painful specimen of savage barbarity—the torturing and burning of an inoensive female, who had fallen into the hands of the merciless foe. The wife of Alexander M’Allister, who had been taken at Tuscarora valley, was the unhappy victim. The same Indian who had killed my mother, tied her to a sapling, where she was long made to writhe in the flames. I knew the Indian to have been the murderer of my mother, from her scalp, which hung as a trophy from his belt. Before these unfeeling wretches had satisfied themselves with the slow but excruciating tortures they caused this woman to endure, a heavy thunder-gust with a torrent of rain came on, which greatly incommoded the Indians. Mrs. M’Allister most earnestly prayed for deliverance, but cruel are the tender mercies of the poor unenlightened savages. They however, sooner no doubt than they intended, when they saw that their fire must be shortly extinguished, shot her, and threw her remains upon the embers. They told me that they had brought me to behold this sight, on purpose to show me how they would deal with me, in case I should ever attempt to run away. Soon aer these events, I went with my companions to Fort du Quesne, where I remained a number of days, and ascertained that the French and Indians daily drew fieen hundred rations. M y next remove was to Kuskuskin [Hog-Town] on the Mahoning, a considerable distance above its confluence with the Big Beaver, where I stayed till the following spring. At this place my life was, for a period, in great jeopardy. I had inadvertently said that I had heard that the white people were coming against the Indians. Bisquittam’s brother, by name Mi-us’-kil-la-mize, was at the place, and his squaw had heard me state the rumor I had heard. She had conceived a violent prejudice against me, and was determined that I should be burnt. A little white girl, about twelve years old, who had been taken in Tuscarora valley, was instructed by the enraged squaw to tell Bisquittam, on his return from Shenango, whither he had gone to tarry a little while, that I said, that he hoped the white men would come against the Indians, and that I wished to run away—adding that, if she did not say all this to Bisquittam, she should be burnt. The little girl told me what a lesson Hugh Gibson’s Survival Story & Interview

5/9/2018 Hugh Gibson’s Survival Story & Interview

https://www.ancestry.com/mediaui-viewer/tree/9182186/person/6572603152/media/64ccf070-bec2-4f7e-8fc0-d0c931d25e15?_phsrc=cco22680&_phstart=successSou

she had received from the squaw. I told the young captive to say no such thing, but to say that I loved Bisquittam, his brothers, cousins, and friends, and that I had no intention to run away. M iuskillamize ordered me to go into the woods and hunt for his horse, which I might know from others by his large bell; and I should ride him to Shenango, there to be burnt by Bisquittam, to whom he had previously sent word, impeaching that me his white brother spend three days, with a sorrowful heart, hunting for the beast, but I did not find him. In the mean time Bisquittam caused information to be given that he would return to Kuskuskin, to burn me at that place. H e accordingly came, and I was standing at the door as he rode up, his face painted black, and vengeance sparkling in his eyes. His first salutation in English, which he well understood, was, ” G—d d—n you ; you want to run away, do you ? The white girl will tell me all about it.” She was called, and I went into the house; but was in a situation to hear all that passed, yet unknown to Bisquittam. The little captive was faithful in stating what I had told her. Upon this, Bisquittam called for me to come out. I made no reply. The call, in a louder tone of voice, was repeated once or twice. At length I answered, and made my appearance. Bisquittam, speaking with great mildness and aection, said, “Brother, I find the Indians want to kill you. We will go away from them—we will not live with them anymore.” We then withdrew some d istance, to a common, and erected our tent and kindled our fire, living by ourselves. Thus I providentially escaped the most horrible kind of death ever inflicted by the savages. I n the spring of 1757, I went to Soh’-koon, at the mouth of the Big Beaver, where I and my brother Bisquittam spent almost a year. At this place Bisquittam took a Dutch captive for his wife. Myself, and Hezekiah Wright, another captive, here cherished many serious thoughts of attempting an escape. Wright, to e ncourage me in the enterprise, told me that he would teach me the millwright’s trade, and would give me forty dollars. In pursuance of our object, I took a horse, saddle and bridle, belonging to the Indians, and set out, intending to cross the Ohio river, Wright on the horse, and I by swimming. This was in the autumn of 1757. We had not proceeded far before Wright began to rue the undertaking, well knowing the dreadful consequence if we should fail to accomplish our purpose. We soon came to the conclusion that it was prudent to abandon our hazardous project; and so we returned to our companions, before any suspicions had been excited. S ome Indians came to. Fort McIntosh (now Beaver), and said in council, that, a white man had run away, followed by two dogs ; adding, that they supposed he would kill one of them and eat it, and aerwards the other. I t having been noticed that myself and Wright were oen in close conversation, we were suspected of an intention to abscond. Bisquittam had no doubts on the subject, and gave vent to his indignation by English oaths and curses, which he had learned of his white fellow creatures; for the Indians have no words in any of their dialects for cursing and swearing. He then gave orders to the Indians to take me away, and burn me. They took me and led me to the common, where they whipped me with a hickory stick till my body was perfectly livid. One of the Indians told another to go and get some fire, and they would burn me. I now thought it proper to attempt an apology, which I hoped would be satisfactory, for my associating so much with Wright. I told the Indians that the reason why I was so frequently with Wright was, that he was a very ingenious man, and we were mutually contriving how to make a plough, like those used by white men, in order to plough in the rich bottom land, and to raise a great crop of corn. Upon this r epresentation, the Indians told me that I must not be angry with them for what they had done; that Bisquittam was a great man; and that they must do whatever he commanded. They then, to make some amends for the flagellation they had given me, and to secure my future friendship, presented me a new shirt and a pair of new leggins. O n a certain time, Bisquittam came to me, where I was busy making clap-boards, and said, ” You good-for-nothing devil, why do you not work and kicked me down, and trampled me under his feet. At length I, aer having borne his abusive treatment for some time, looking up with an unruled countenance, and in a so and gentle manner, merely saying’, ” I hear you, brother,” my master was instantly disarmed of his rage, and showed me the greatest kindness. I n the fall of the year we went back to Kuskuskin, where we spent the winter. In the ensuing spring, an Indian, called Captain Birds, from the circumstance that he had two birds painted, one on each temple, was making arrangements for going to war at Tulpehokken. I said that I wished to go too, but was opposed by Bisquittam. All contemplating this expedition were volunteers. I attended the war-dance every night with the Indians. One of my cousins, who encouraged me in my purpose of joining the war party, advised me to spend a few days in hunting, stating that Bisquittam would soon be out of the way, as he was about to set out for Koh-hok-king, in the neighborhood of Painted Post.”, then,” said he, ” you can go.”I and a little boy, of twelve years of age, went on a hunting excursion, were absent three days, killed two turkeys, and returned; but Bisquittam, whether suspecting the plan or not is unknown, was still at the place. I, with the little boy again took a tour into the woods. We reached an Indian sugar camp the firstevening, stole a horse and a bag of corn, rode seven miles to a cranberry swamp, tarried there seven days, parched and ate our corn, threw away the bag, killed one turkey, and returned to the sugar camp. Here we heard a gun. I discharged his, which led the Indian who had first fired to come to us, as we expected and wished. My first inquiry was, whether Bisquittam had set out for Kohhokking, and, being answered in the negative, I sent the little boy to the Indian town, and the next morning took the nearest course to Fort McIntosh. I went to the warriors, among whom I saw the cousin who had encouraged me to join the war party. Bisquittam, having ascertained that I was at McIntosh, sent word to the Indians that if they took me away so that he should lose me, he would make them pay him a thousand bucks, or return him another prisoner equally good. H aving spent several days with the warriors, till they were about to repair to Fort du Quesne for their equipments, they told me I should not go with them. One of the savages held a tomahawk over his head and said he would kill me on the spot, and then he would not have the trouble of going—and added, that he only wished to go to the war, in order to have a good opportunity to desert from the Indians. The cousin before-mentioned said, in my behalf, that he should be with me all the time, and that there would be no danger of my escape, even if I wished it. Upon this, I went over the ferry and accompanied them about five miles, where I saw Bualo Horn, another brother o f Bisquittam, who asked the Indians if I was going with them to the war. They replied that they could not persuade me to go. Bualo Horn said that, aer he had d one eating, he would talk to me about it. This chief shortly aer took me aside and said, “Hughey, are you going to the war ? I tell you not to go. You and I are going into the country in the fall. I shall go to fight the Cherokees, and you shall go with me. Stay with me, your poor old sick brother. Get me some pigeons and squirrels.” I replied, “I will do whatever you wish me to do.” He then said to me, “Take my negro man and canoe, and fetch me some corn from McIntosh.” In fulfillment of this direction, I went to that Fort, where I saw King Shingiss, a brother

5/9/2018 Hugh Gibson’s Survival Story & Interview

https://www.ancestry.com/mediaui-viewer/tree/9182186/person/6572603152/media/64ccf070-bec2-4f7e-8fc0-d0c931d25e15?_phsrc=cco22680&_phstart=successSou

of King Beaver, and Bisquittam. King Shingiss said to me, “Are you here? You are a bad boy. We are all sick. You must go as an express to Kuskuskin, to tell the people that three Indians have been killed and three wounded by the Cherokees, and you will occupy my tent till I come.” I, taking a loaf of bread and two blankets, immediately set out and travelled on foot to the place, a distance of thirty-six miles, in six hours. The Indians said that they would all come to him to hear the news, that they might have the truth. Here I remained, dwelling in King Shingiss’s tent till autumn. O n one occasion King Shingiss and I went into the woods, in pursuit of any wild animals we could find. I killed a large bear, much to the mortification of the former, as he killed nothing, and thought it highly derogatory to his character to be outdone by a white fellow hunter. While on this excursion, I told King Shingiss there would shortly be a peace with the white men. “How do you know?” I replied, “I dreamed so.” A few days aer, Frederick Post, in company with Bisquittam, came to Kuskuskin, with a view to settle the preliminaries of a peace. This was in the latter part of 1758. Ever aer, while I continued with the Indians, I was called a prophet. I was afraid to see Bisquittam, because I had wished to join the Tulpehokjsen warriors, contrary to his master’s will. However, he approached me aectionately, and said, “How do you, brother? I have brought a large bear skin, and make a present of it to you to sleep upon.” Bisquittam received me kindly and I thanked him for the donation. We both repaired to Fort McIntosh, where we lived till sometime in the winter.It was in the autumn of 1758, that General Forbes, being at Loyal Hanna, sent Captain Grant, with three hundred men and three days’ provisions, to view the ground and ascertain the best route to Fort du Quesne. Grant exceeded his orders, being sanguine of success, and rashly urged his way with the expectation of taking the Fort. He was met and pursued by the French and Indians on or near the hill in Pittsburg, which bears his name to the present day. Grant killed many of the enemy, but not a few of his own men were destroyed and taken. He also became a captive and was sent to Canada. The r esidue of his forces retreated to Fort Ligonier. The Indians, having strong suspicions that their brother intended to desert them, about the middle of October, 1758, took him to Kus’-ko-ra’-vis, the western branch, which uniting with White Woman’s Creek, the eastern branch, forms the M uskingum. There was my home till the beginning of the ensuing April, when I found means to make my escape. At this place was David Brackenridge, recently taken at Loyal Hanna. Here also were two German young women, who had been captured at Mok-ki-noy, near the Juniata, long before myself. The name of one was Barbara. The other was called by the Indians Pum-e-ra-moo, but she was from a family by the name of Grove. It was at length determined by the inhabitants of the forest that the latter should marry one of the natives, who had been selected for her. She told me that she would sooner be shot than have him for her husband, and entreated me, as did Barbara likewise, to unite with them in the attempt to run away. They proposed a plan, which they supposed would aord facilities for the desirable object. They were to feign themselves indisposed; when it was expected that they would be ordered to withdraw from the society of Indians, and to live by themselves for a season. The project succeeded according to expectation. On their making the representation, as agreed, the Indians told them to go and kindle their fire at some distance from them. T hey selected for their purpose the bank of the Muskingum, just below the confluence of the two branches of the river. The night was appointed for their flight. In the mean time I, returning late one evening to his master, told him that I had seen the track of his horse, which I knew by the impression of his shoes, no other horse in that quarter being shod, and that I had followed the track for some time without being able to overtake him. I then proposed to Bisquittam to go in search of the horse, and, having found him, to spend three days in hunting; to which my master acceded. It was further agreed that Bisquittam should spend some time in a meadow, a little below the fire of the two women, in digging hoppenies [i. e. groundnuts], and that I should return that way with the horse and venison, and take the hoppenies and meat home. Bisquittam furnished me with a gun, a powder-horn well filled, thirteen bullets, a deer skin for making moccasins and sinews to sew them, two blankets, and two shirts, one of which was to be hung up to keep the crows from pillaging the venison. A er breakfast I started, and instead of going in pursuit of the horse, took my course leisurely to the women’s camp, seven miles, where I arrived about ten o’clock in the evening, and found Brackenridge with them, according to previous arrangements. As I travelled, in the evening I discovered some of the natives, though they probably did not notice him. I saw the fire, where Bisquittam had been digging hoppenies during a part of the day, perhaps not more than sixty rods from the spot whence we were to attempt our departure. The utmost caution, prudence, and dispatch were indispensable in the hazardous enterprise; for, should our object be discovered, nothing could save us from the stake. It was about the full moon. The Muskingum River was very high, and there were two ras near the women’s fire. We unmoored one, and it soon went down the river. We entered the other with our accoutrements, the women taking their kettle, crossed the Muskingum, and let the ra go adri. We travelled with all possible expedition during the residue of the night in a southerly direction, in order to deceive the Indians, in case they should attempt to follow us. In the morning we steered a due east course. O n the second day we mortally wounded a bear, which, “in the contest, bit my leg, and got’ into a hole, whence we could not obtain it. We however killed a buck, the best part of which we carried in a kind of hopper, made of his skin. On the third day, at night, we ventured to make a fire, roasted and feasted upon our venison. On the fourth day we shot a doe, took the saddle, reached the Ohio River above Wheeling, made a ra with the aid of our tomahawks, passed over, and entered a deep ravine, where the land above us was supposed to be more than three hundred feet in height. Here we kindled a fire, cooked and ate our meat, and spent the night. I n the morning, with much diiculty we ascended the steep eminence, and set our faces for Fort du Quesne, keeping on the ridge not far, in general, from the Ohio. We saw the fresh tracks of Indians, when opposite to Fort McIntosh, but were not molested, and probably were not seen by them. On the fieenth day a er leaving the Muskingum, in the evening, we arrived in safety on the banks of the Monongahela, directly opposite to the Fort, and called for a boat. The people were suspicious of some Indian plot, having once before been grossly and treacherously deceived. We were directed to state our number, our names, whence they had been taken, with other circumstances, for the satisfaction of the garrison, before our wishes could be gratified. Brackenridge told them that he was taken at Loyal Hanna, where he drove a wagon numbered 39. Some of the soldiers knew the statement to be correct. I informed them that I was captured near Robinson’s Fort, and that Israel Gibson was my brother. Some present were acquainted with the latter. The females represented that they were from Mokkinoy, and that there were but four of the party. U pon this, two boats with fieen men well armed, crossed the Monongahela. Their orders were, in case there should appear to be more than four, to fire upon us. On approaching the western shore, the boatmen directed us to stand back upon the rising ground, and to come

5/9/2018 Hugh Gibson’s Survival Story & Interview

https://www.ancestry.com/mediaui-viewer/tree/9182186/person/6572603152/media/64ccf070-bec2-4f7e-8fc0-d0c931d25e15?_phsrc=cco22680&_phstart=successSou

forward, one at a time, as we should be called. In this way we were all soon received and carried to Fort du Quesne, where our joy was such as may be better conceived than described. It was not long before we were all restored, like persons from the dead, to the arms of our relatives and friends. H ugh went to Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, where he spent two years with his uncle, William McClellan, and at the age of 21, on 14 June 1762, married Mary White , a daughter of the widow Elizabeth White. They then repaired to his late mother’s plantation in Shearman’s Valley, two miles from Robinson’s Fort. High withdrew, aer having wrought upon that place two years, in consequence of hearing that the Indians were intending to come and take him again into captivity, and lived in Lancaster County during the Revolutionary War. At the age of fiy-three years, Hugh moved to Plum Creek, on the Alleghany, and thence to Pokkety, Western Pennsylvania being free from all fears of Indian depredations. P er the 1790 U.S. Federal Census, the Gibson family was living in the Hopewell, Newton, Tyborn & Westpensboro, Cumberland Co, Pennsylvania area; Free White Males under 16: 2, Free White Males 16+: 2, Free White Females: 4. T he Gibsons settled, on the 17th of April, 1797, in Wayne township, Crawford County, seven miles below Meadville, on the eastern bank of French Creek, his p lantation comprising a part of Bald Hill. I n the 1800 U.S. Federal Census, the Gibsons were living in Meadville, C rawford Co, Pennsylvania; Free White Males 45+: 1, Free White Females 10-15: 1, Free White Females 26-44: 1. M ary died about 1820 in Wayne, Crawford Co, Pennsylvania. On 7 August 1820 the 1820 U.S. Census was taken, finding the Gibson family in Crawford County; Free White Males 10-15: 1, Free White Males 45+: 1, Free White Fe-males under 10: 1, Free White Females 16-25: 1, Free White Females 26-44: 1, Free White Females 45+: 1. H ugh died at the age of 85 on 30 July 1826 in Wayne, Crawford Co, P ennsylvania. M ary and Hugh had six children: Elizabeth, Mary, William, Andrew (1765-1828), Israel (your direct line ancestor), and Sarah (1786-).

I believe we are related. My great grandmother was Mary Elizabeth Gibson who married in 1881 a blacksmith, Amos Whiteman. Mary and .Amos first lived in Farmington, Cecil County, later moved to Sylmar, Md although the physical location of their home and blacksmith shop was just a few yards away in PA. Mary and Amos’s youngest daughter, Mabel, married a neighbor, John J. Reynolds. They were my maternal grandparents. I understood from family lore that Hugh Boyd Gibson (wife nee Gillespie) were Mary E.’s parents but have never researched that family. Incidentally, one of John J.’s brothers was named Charles Craig Reynolds. Mabel’s brother Bill Whiteman took over his father’s business and I remember vividly our visits there. In fact, Uncle Bill used to make shoes for the horse my husband owned before we met. As a wedding gift my FIL had andirons made from them. We still live in the Nottingham, PA area and would be interested in exchanging information. I also remember vaguely a distant relative of Mom’s named David Gibson who lived in Cecil County. He had a daughter named Ruth who was in the Rising Sun HS band with me. Both of us played clarinet.. We lost touch years ago.

Allyn,

I have located the information Lydia Founds gave us before she died about Hugh (1818-1860) and Mary Elizabeth (1823-1857) and sketchy information about their 6 children. She has nothing about James other than his name, but included another daughter of Hugh’s and Mary Elizabeth’s named Providence (1846-1889) married to John Thomas Caldwell (1839-1913). Did you know about Providence? My gr-grandparents Mary Elizabeth Gibson (1855-1918) and Amos Whiteman (1855-1930) are buried at Hopewell. My mother said Mary Elizabeth died in the flu epidemic. They had 6 children. Somehow I lost the emails we exchanged earlier this month. Would you send me your snail mail addy so I can send you the information about my line if you are interested? It is not on a database on my current computer. Looking forward to hearing from you!

It was good to see what some of these cemetaries look like. Of all of my patrilineal line the Janney Quakers were easiest to find, and one of the few to be reliably traced to the old country. Many like Archibald, Reynolds, Pratt, Bauer, Gray, Shipley and Musgrove just evaporate in the 19th Century. Would trade some well painted figures to find out what happened to Henry Reynolds who married as her first husband in 1880 Sarah Jane Archibald (1854-1946).