Late last year I had a dream that I found the grave of Captain Thomas Feenhagen, my great-great-great-grandfather.

Feenhagen, the father of my my great-great-grandmother Susan and grandfather of my great-grandfather Allyn Gardner, was a sea captain. He commanded a merchant ship, the bark Seneca, in the 1850s and 1860s. From what little I’ve been able to glean from the records, he plied the seas between New York and South America (often Montevideo), his ship was stopped off Cape Hatteras by the Navy a few times during the Civil War (to make sure he wasn’t smuggling contraband to the Confederacy), and in 1852-3 he sailed to Australia and from there to San Francisco. I won’t go so far as to say that he sailed around the world, but he certainly saw the Antipodes. He was a prominent figure in the eastern district of Baltimore, according to his obituary, and at the time of his death he was an investor in a railroad line through Fells Point. Feenhagen was first-generation American; his father had emigrated to the United States from Oldenburg, Germany just after the Napoleonic Wars. He died in 1870 in somewhat gruesome circumstances; a spar aboard a ship in harbor broke loose and crushed his skull.

Feenhagen, by the way, was an affectation. His father’s name was Bernard von Hagen, which was anglicized into Fenhagen. Thomas Feenhagen’s brothers used Fenhagen (and their descendents are in the St. Mary’s area). Feenhagen’s own children used Fenhagen, though not consistently; his daughter Laura is listed in the Washington City Directory of 1887 as “Feenhagen, Laura O.,” even though every other record I’ve seen gives her maiden name as “Fenhagen.”

The dream of finding Feenhagen’s grave was vivid, and it put the idea in my head that Feenhagen was findable. I assumed he was buried in Baltimore, but where? The three great 19th-century Baltimore cemeteries were Greenmount, in the center of the city, Loudon Park, on the western side, and Mt. Carmel, on the eastern side. Mt. Carmel Cemetery on Baltimore’s eastern side seemed a likely possibility.

Mt. Carmel Cemetery is located on O’Donnell Street. When I moved to Baltimore in 2006, I worked for several months on O’Donnell Street, at the old National Bohemian brewery, and I would pass Mt. Carmel on 95 every day. I remember having the occasional thought at the time, “I should visit there and poke around.” I knew that some of my Baltimore ancestry was German, Highlandtown (a neighborhood near where I worked) was Baltimore’s 19th-century German neighborhood, I had the feeling then that I could have a link to Mt. Carmel.

And, of course, I never investigated it. After I left Elder Health in March of 2007, I don’t think I’ve been on that side of Baltimore at all — or even on that stretch of 95 inside the Beltway — even once.

After the dream last year, I decided that, when an opportunity presented itself, I would poke around Mt. Carmel and see what I could find. The dream had some specific details: there was a curb, the trees were leafy, when I left the cemetery there was a hilly road through an rundown neighborhood, his grave was near-ish the cemetery entrance and quite near where I parked the Beetle. Dreams are dreams, though, and maybe they shouldn’t be taken having any sort of meaning, but I’ve had an odd and uncanny ability in the past to find things I don’t expect.

The weather forecast for the weekend decided it for me. Saturday, at least, was going to be sunny and seventy-five, and so plans were made.

Mt. Carmel, it turns out, what not the place at all. Nothing about it matched my dream. And if Feenhagen is there, he is either unmarked (possible… but my dream!) or he is unreachable due to the condition of the cemetery.

To be frank, Mt. Carmel Cemetery is a place of sadness and neglect. Large parts of it are wild; headstones, some standing, some not, stand overgrown with vines and inaccessible among briars and young trees. What’s truly surprising, given the state of the cemetery, is that Mt. Carmel remains an active cemetery; among broken and neglected graves from the 19th-century are headstones for people who died within the last ten or fifteen years, who have visited recently and left balloons and flowers and other such tokens. In fact, I encountered a family visiting their recently deceased loved ones as I was leaving.

I did not find Captain Thomas Feenhagen. Nor did I find William Krauch, the second husband of the great-grandfather Allyn’s sister Isabelle, who I do know is buried there, as is one of Krauch’s daughters from his first marriage. Yet, the visit was not a complete waste. There were some interesting things to see. Many of the headstones had German names — not unsurprising, given the proximity to Highlandtown — and some headstones were carved entirely in German. There were also some headstone styles that were completely unfamiliar to me.

And it was a nice spring day, and spending those days outside is never a waste.

Mt. Carmel was, in a word, swampy. There had been rain earlier in the week, but nothing to justify the amount of standing water. The drainage seemed poor.

A number of headstones in the cemetery were, as I mentioned above, carved in German. The United States has always been a bilingual country; what the dominant secondary language (other than English) is depends on when in history you are. In the 19th- and early 20th-centuries, that secondary language was German, and it was largely stamped out during World War I. Until the 1920s, Baltimore had a thriving German-speaking community and daily German language newspapers, so it wasn’t surprising to me to find German language headstones from the late 19th- and early-20th-centuries.

I was struck by the look of these headstones, too. I hadn’t seen anything that looked quite like these elsewhere, but this style was quite common at Mt. Carmel. I’ve found that cemeteries in different areas have different headstone styles. There are some commonalities, but there’s a unique style that I won’t see elsewhere. Local stone masons had their own, unique style, and people would go to the mason in the neighborhood to have the headstone made. Carving these must have been quite intricate, because so much of the information on the stone is done in relief.

Here’s another example of the headstone above, though the relief carving at the top of the stone is not curved over to the extent as in the German example. The two to the left were even more interesting. There were probably a dozen of these that I saw in the cemetery. I also saw several that were broken; the carved piece atop the base was missing, leaving the metal spike that attached the sculpture to the base.

Here’s another style of headstone I’ve never seen before. It’s similar to the one above, but not identical. It was somewhat common and all generally dated to between 1905 and 1920. There’s this — what’s the word I want? — jaunty relief carving of the name on the face, and the carving of “Mother” and “Father” on the curved top has an old-time look. (It reminds me of the typography of the Boston Red Sox or Brooklyn Dodgers “B” logo. This font style is common on headstones I call “railroad ties.”) I say “jaunty” because the way the names are carved was loud and brash and, frankly, fun, like something you’d find on a circus poster circa 1910. Some of these were carved in German, and they looked exactly the same, with the same jaunty carving.

This is what I call the “railroad tie.” It’s ground level, about five feet long and a foot wide, and no useful information at all except a name. I’ve seen these around Baltimore — they’re here, at Loudon Park, and at Cedar Hill — so they’re clearly not the unique style of a local stonemason. The Henry Hardy who could be my great-grandfather Allyn’s brother is marked with one of these at Loudon Park. One problem I’ve noticed with these is that they can sink into the ground and become unreadable. And, of course, as I said, they have no useful information whatsoever.

This was another unique style to Mt. Carmel — a cylindrical monument. There were two of these that I found — there could be more, in the overgrown portions of the cemetery — and it was the same color and carved the same way, so it’s safe to say that these came from the same mason.

The Natty Boh building can be seen through the trees to the right of the monument. To the left through the tree is the old First Mariner building.

John Cathcart, War of 1812 veteran. This was close to unreadable, but it does say that Cathcart participated in the defense of the city in 1814.

Another example of German language headstones.

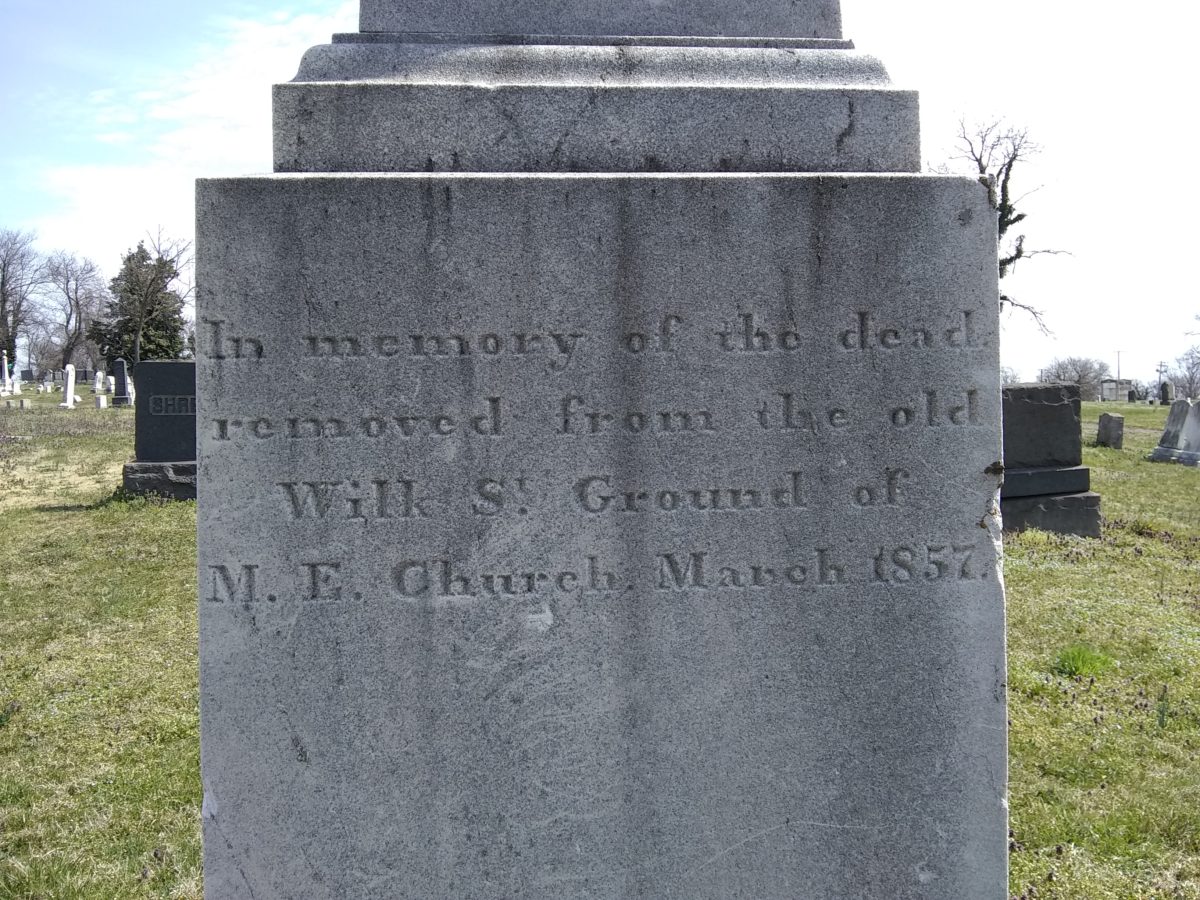

A monument to the deceased relocated from the closed cemetery of Wilkes Street Methodist Episcopal Church in 1857. (Wilkes Street is now known as Eastern Boulevard.) To give you an idea of the state Mt. Carmel fell into, according to this account, this monument was only rediscovered in 1996. I can only imagine that a tree knocked the obelisk way off its base.

The inscription on the Wilkes Street Methodist Episcopal memorial. This inscription appears on the east and west faces of the monument. (This is the west face.) The north and south faces are blank.

My guess — this is a generic marker for sailors lost at sea, placed by the Port Mission in Fells Point a century-plus ago.

Mt. Carmel Cemetery abuts Interstate 95. To left, beyond 95, is the Natty Boh Building.

As a fan of the writer Ring Lardner, a friend to F. Scott Fitzgerald and an inspiration for the early Ernest Hemingway, probably best known today for his baseball fiction of the 1910s, I was amused to find this monument to the Ringgold family. (Lardner’s first name was Ringgold.) The faces on the left and right sides of this monument also named their deceased children, seven total.

“Father Time,” the monument for James Belden, the cemetery’s architect. I was parked about forty feet to the right. And, of course, there was the trash behind him.

Mt. Carmel seemed to be a dumping ground for the neighborhood’s garbage. And there were signs that kids used the cemetery as a place to drink.

There are large parts of the cemetery that are inaccessible. Trees and weeds grew up around the headstones, thanks to decades of neglect.

Nature unchecked destroyed this cemetery.

These were people who were loved in life, and they were abandoned in death.

Yet, there was beauty here.

The search for Captain Thomas Feenhagen will continue. Greenmount will be next, sometime this summer. There are other Fenhagens there, so we shall see.