With the affiliated minor league baseball season cancelled — and, in Pennsylvania, the unaffiliated season, too — my local baseball teams have been having non-baseball activities, including movie nights on the weekends. Sit in the outfield, socially distance, watch a film on the video board.

I’ve not done one of these, though I was mildly tempted by Raiders of the Lost Ark when the York Revolution showed it a few weeks ago. Fortunately, I needn’t have bothered; that night was rained out.

When I was at Diamond’s offices on Wednesday — I go in about once a week, usually when I need to print something out — I bought a ticket for the Harrisburg Senator’s Friday night’s showing of The Sandlot as this gave me an opportunity to go up to Harrisburg and FNB Field, which I’d not done since last year’s Eastern League playoffs. For those unfamiliar with The Sandlot, it’s a 1993 film about a group of kids who have a sandlot baseball team in California in the early 1960s. I saw it the weekend it came out at River Ridge Mall in Lynchburg and not since. I remembered almost nothing about the film — it was told in flashback like The Wonder Years or Oliver Beane, someone said “You’re killing me, Smalls,” James Earl Jones was in it, and there was a dog — and though I had no particular affection for The Sandlot I recalled being entertained by it when I saw it when it came out.

My drive from York to Harrisburg was later in the day than I’d ever gone up to FNB Field, and the late August twilight felt odd. My neighbors’ son was sad that I had to leave to head up to the ballpark — he wanted to talk about cats, as there’s a stray cat that likes to sleep in their garden. I felt happy taking the Lemoyne exit off of 83, seeing the skyscrapers of downtown Harrisburg, taking the turn through Lemoyne, turning onto the Market Street Bridge. Even the “Next Game” banner at the turn into the City Island parking lots brought a smile to my face. I climbed the steps from the parking lot, and almost everything about this felt “normal,” even though so much had changed, myself included, since I was last here. In September, there wasn’t a global pandemic. In September, I wasn’t half-blind.

Had this been a baseball game I’d have been there when the gates opened, but for this I was more leisurely, getting to the gates about quarter after seven. Entry to the stadium was through a side entrance, and after being handed a raffle ticket (which I promptly lost) and signing a waiver to release the team from any claims if I were to catch COVID I made my way onto the field. There was a decent crowd, and some people were playing catch on the outfield.

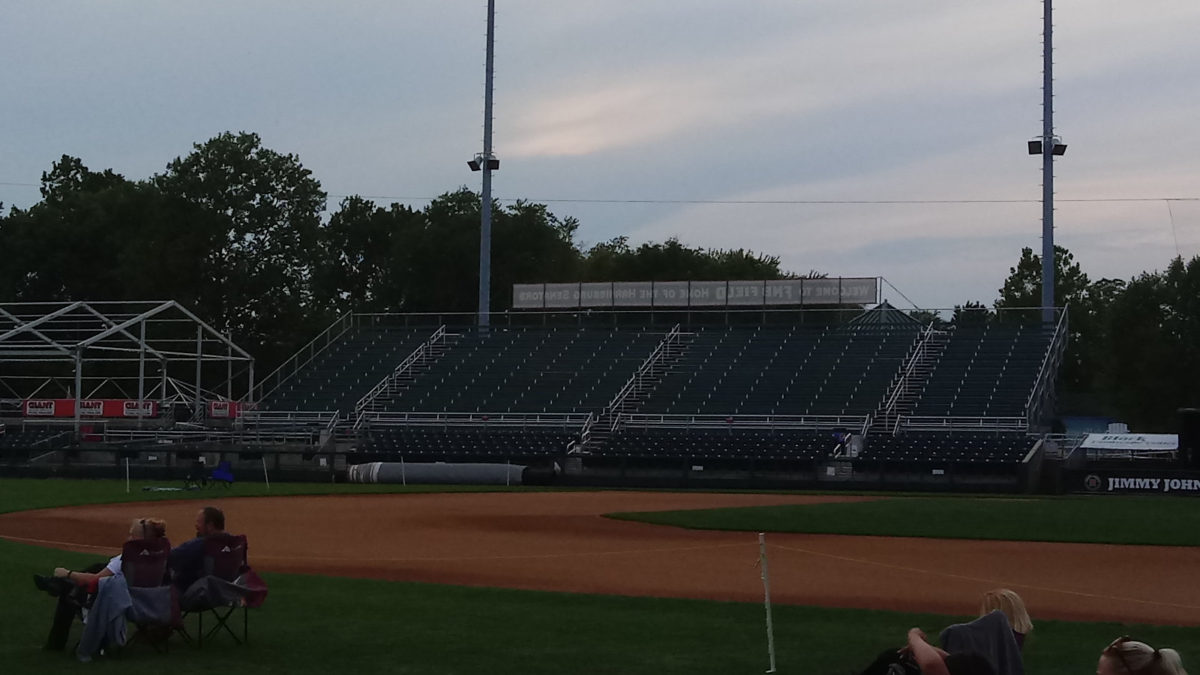

I’d actually never been on the field at FNB Field — or any minor league ballpark, for that matter — before this. I staked out a place in the left field corner, threw down an old school Washington Nationals beach towel, and took a walk around the outfield.

One of the first places I stopped was below the first base bleachers. My usual seat is up there — two thirds of the way up, along the middle aisle — and I’ve missed it. I’d like to think it has missed me, but it hasn’t. It’s an inanimate object. It’s an aluminum bench. No feelings there.

Still, I stood near the wall near the first base boxes, looked up, and felt a little sad. In another world, I’d have used the tickets I bought at the beginning of March, and I’d have spent a dozen summer afternoons and evenings this year there.

A concession stand was set up on the third base side. They offered popcorn, ice cream sandwiches, and soft drinks. I bought one of each. The popcorn was cold and a touch on the salty side.

The main concourse was not open to the public, except for the restrooms on the third base side. I stood at the railing there before the film began and looked out across the Susquehanna at downtown Harrisburg and the capitol dome.

Just before eight o’clock, The Sandlot began.

The Sandlot is not a good movie.

Yes, I am aware that it is beloved and often held up as one of the classic baseball films. Yes, I know that I am not its target audience. But I know a bad movie when I see it.

About midway through the film I had formulated a mental shorthand, an elevator pitch for The Sandlot — “The Goonies meets The Natural, by way of The Wonder Years.” There’s a lot of incident, a smattering of character, but very little plot.

The story goes something like this. In the early 60s, a boy named Smalls moves with his mother and stepfather, with whom he has a nervous and distant relationship, to the Valley, just before the end of the school year. He despairs of making friends, but quickly meets a group of boys, led by Benjamin Franklin Rodriguez, who have a sandlot baseball team. Though Smalls has no baseball skills whatsoever when the movie begins — he can’t even throw a baseball — he quickly becomes a part of this team and friends group. They have a number of misadventures over the summer, climaxing with the attempt to recover from the junkyard adjacent to the sandlot field an autographed Babe Ruth baseball, which Smalls took from his stepfather’s study for the team to play with, not realizing what it was, that unleashes a monstrous dog on the town. This is all framed by a sequence in the film’s near-present (probably mid-1980s at the latest based on character ages) in which we learn that Smalls has become an announcer for the Los Angeles Dodgers and Benjamin Franklin Rodriguez plays for the Dodgers.

Typed out in that way, The Sandlot doesn’t sound too bad. The problem, from a writing standpoint, is the way its script spends its middle act on “they have a number of misadventures over the summer.” There’s the swimming pool escapade, the town fair incident, the challenge by another team who’s so professional they have uniforms. These sequences all develop character as they show the sandlot team bonding and hanging out together, but they don’t push the plot anywhere, nor they do they have any relationship to the climax and resolution. Except for the treehouse party where the story of the junkyard dog is told, the entire middle act is a waste of time. The first act shows up that Smalls is inept as a baseball player, and that’s completely glossed over by the rest of the film. The climax of the film depends on Benny’s speed at running, yet we never see him run the bases in the baseball scenes so we have no idea whether or not Benny can outrun a dog through town for twenty minutes. When I described the film as being full of incident, that’s what I mean. The Sandlot is structured episodically, a problem for the characters is introduced, and it’s resolved within ten minutes and with no narrative effect on the rest of the film. It’s not a movie that develops over its running time. It’s a movie that’s a string of nominally related scenes.

The irony of spending so much of the middle act on character is that the characters in The Sandlot are so anonymous. I can name five characters — Smalls, Benny, Squints, Wendy Peffercorn, and the ghost of Babe Ruth — and can remember a sixth (the catcher), and after that I’m hopeless. The rest of the sandlot team needs to be there so there’s nine kids, but they’re insignificant.

James Earl Jones’ character is curious. We learn — spoilers for a twenty-seven year-old movie — that he played baseball at a high level several decades before the film (a career that was cut short when he was beaned in the head with a fastball and rendered blind), that he knew Babe Ruth (Jones’ character refers to Ruth as “George” several times and there’s a photograph of him with Babe Ruth, both in uniform, on the wall of his study), and that he claims that people said that he would break Ruth’s home run record. Here’s the problem — professional baseball wasn’t integrated until 1947, when Jackie Robinson took the field for the Brooklyn Dodgers, and Jones and Ruth could not have been contemporaries (as the film indicates) in the integrated era as Ruth’s playing career ended in the 1935 and he died in 1948. Now, Jones’ character could have played in the Negro Leagues, and he could have known Ruth (who was known to socialize with black ballplayers and I believe may have played in some exhibitions against Negro League players), and people could have said that if he had been able to play in the American or National League then he could have broken Ruth’s home run record. But that’s not the way the film presents it. The Sandlot, like Field of Dreams before it (as Craig Calcaterra expounds upon here), pretends that baseball didn’t have a color line, pre-1947. Now, I didn’t catch if Jones’ character was named, and it’s tempting to think that his character in The Sandlot is the same character he played twenty years earlier in The Bingo Long Traveling All-Stars & Motor Kings where he played a Negro League slugger inspired by Josh Gibson. Squint just so, and The Sandlot becomes more interesting as a sequel to Bingo Long.

As an aside, Babe Ruth, after his playing career, hoped to manage a major league baseball team, but he was never offered the opportunity. It’s been speculated that the reason why Ruth never managed is that, due to his friendships with black baseball players, that Ruth would have pushed to break the “gentleman’s agreement,” sign black players, and field an integrated team in the 1930s.

The film’s other problem is its narration. I’m not sure than any of it was necessary; it’s lazy filmmaking in that it allows the film to “tell, not show” its story. The actor is dull to listen to, and if there were a drinking game where you take a shot every time the adult Smalls says, “the biggest pickle,” you’d be dead of alcohol poisoning by the time the film apes The Natural‘s shattered baseball.

I realize The Sandlot is a film people love and remember fondly. I know I’m not its audience. I realize my views cut across popular opinion and will not endear me to others. The cast is fine. But, on basic writing and filmmaking levels, The Sandlot is a bad film.

At least there was a lovely sunset on City Island last night. And when the film didn’t engage me, which was often, I’d put on hand on the outfield grass and run my hands across it.

After the film, I walked across the Walnut Street bridge into downtown Harrisburg. It’s something I enjoyed doing, as it gave me a chance to let the post-game traffic off the island dissipate.

There were a few boats on the Susquehanna at that hour. On the eastern shore I took a photograph looking back at the stadium. I missed this view, too, but it was different than it would have been on a game night. There weren’t as many lights, as the light towers were not illuminated.

I walked along Front Street to State Street and stopped to look at the capitol building. I thought back to an old photograph of Harrisburg in 1906 that I saw online a few weeks ago — there’s St. Patrick’s to the left, Grace United Methodist a little further up, and the capitol dome.

People were riding bicycles, a man was walking his dog. a woman threw her trash in a can and missed, people sat on the benches, there was a domestic disturbance of some king.

The, too, felt almost normal. The traffic was a little lighter than it might have been a year ago. Some of the restaurants along Second Street that were open weren’t as boisterous. Some of the restaurants and bars were shuttered and dark.

By the time I returned the City Island the stadium was dark and the parking lot was empty. I took my old familiar route home — Market Street to Front Street, and that to 83 South — and it was more difficult than I thought it would be. I have difficulty driving at night now. Sometimes it’s downright terrifying, especially if I have lights in my face. Last night, getting out of Harrisburg, was one of those terrifying times. It wasn’t until I was on 83 south of Reeser’s Summit that I felt comfortable driving.

Despite the terror of driving out of Harrisburg and the underwhelming nature of The Sandlot, I had a nice outing. I was glad to get out and go somewhere that wasn’t the office or the grocery store. True, I couldn’t get comfortable on my towel (my leg fell asleep) and I lost my keys (they fell out of my pocket onto the outfield grass), but I told a woman that I liked her Gerardo Parra blue Nationals jersey and I got to spend a couple of peaceful hours in one of my favorite places.

In these strange times, that’s enough.