On June 9, 1886, the Washington Nationals and the St. Louis Maroons met at Swampoodle Grounds in Washington. That same day, a dozen blocks southeast of the ballpark, following a funeral service that morning in Baltimore, Annie Atwell was laid to rest at Congressional Cemetery in a family plot with the remains of her daughter.

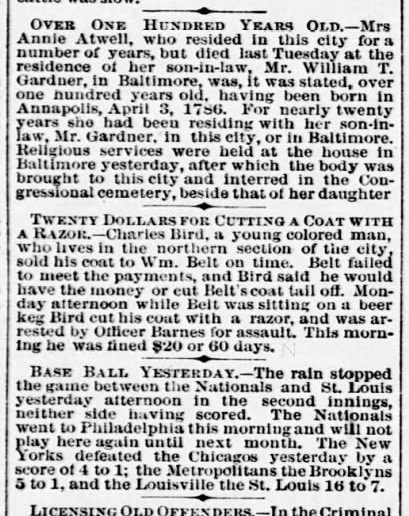

From Washington’s Evening Star newspaper, dated June 10, 1886:

I could have cropped it after the first article, but I was amused by the account of the baseball game in the same column. The Washington Nationals played the St. Louis Maroons at Swampoodle Grounds, a few blooks north east of the Capitol the previous afternoon, and rain halted the game in the second inning. The Nationals of 1886 were an historically bad team, going 28-92 and finishing an eye-popping 60 games out of first place. Little wonder, then, that today’s Nationals don’t claim the heritage of that long-defunct team, though they could. Besides a ballpark with a wonderful name like “Swampoodle Grounds” and the Capitol dome looming over the wall in right center, those Nationals fielded Hall of Famer Connie Mack. An argument could be made that Mack belongs in the Nationals’ Ring of Honor with other greats like Walter Johnson, Josh Gibson, Frank Howard, and Frank Robinson.

But that’s not what I wanted to talk about. My interest is in the top article: “Over One Hundred Years Old.” Mrs. Annie Atwell, who had lived in Washington for a number of years but most recently resided in Baltimore, died at the house of her son-in-law, Mr. William T. Gardner two days earlier, aged one hundred, having been born April 3, 1786.

I had been looking for this — or rather, something like this — for well over a decade. What I was looking for was a death notice, maybe a detail or two, like Atwell’s age, and nothing more.

What I did not expect to find was a whole article like that.

You see, William Gardner is my great-great-grandfather. I’ve visited his grave from time to time the last eight years — I first visited Labor Day 2012 — and William is buried next to Anne Atwell. (I am not descended from Anne; she was the mother of his first wife, Mary Elizabeth, and I’m descended from William’s youngest child with his second wife, Susan.) So I have also visited Anne. I’ve patted the ground and said her name, even though there’s nothing there that would have any idea who or what I was.

And I find the whole incredibly improbable!

But to explain that, first let’s look at what I really was looking for — Atwell’s death notice in a newspaper. Only, it wasn’t in a newspaper I was expecting it to be in. From the Baltimore Sun, June 9, 1886:

I expected to find this — and not that article — in a Washington newspaper, not a Baltimore newspaper, as I believed that the Gardners, including my then-six-year-old great-grandfather, were living in Washington when Atwell died. Specifically, I believed that, due to her age, they were probably living on 11th Street SE.

Here’s what I knew — or thought I knew. Family lore held that my great-grandfather, as a child, lived in Georgetown. No one was exactly sure when, but maybe sometime around 1900. Census records for 1870 and 1880 put my great-grandfather’s parents in Washington in those years. Anne Atwell is living with the Gardners in both census years and is listed on the census forms as the “mother-in-law.” But the census records, while inconsistent in age, which I’ll explore below, all point to a birthdate around 1800. Then, the City Directories — Boyd’s? Or is it Polk’s for Washington? — have the Gardners living from the mid-1860s (when they moved there from Baltimore, during the Civil War) to the mid-1880s at a succession of addresses on 6th Street SE to M Street SE to 11th Street SE. (I explore that, complete with annotated maps, in this blog post.) In 1880, there’s a new addition to the household — my great-great-grandmother Susan’s sister, Laura Fenhagen — and she’s listed separately in the City Directories as well, which becomes a kind of check: “if there’s a William Gardner at this address, and Laura Fenhagen is at the same address, then this is confirmation that this is where they are.”

In the City Directories, there is a shift in the Gardner and Fenhagen addresses to Georgetown, and it happens about 1886. As I said in that blog post, I have no idea why the Gardners move across the city. This moves them away from three of their adult and married and children. I assumed this move from 11th Street SE to M Street NW would have happened after Anne Atwell died. Now, not only do I know she made that move, but she also made a subsequent move from Georgetown to Baltimore.

Why, if by June 1886 the Gardners were in Baltimore, are they in Washington’s City Directory in Georgetown? Production lead times. I work in publishing. Publishing takes time. You have to get your information. You have to set your type. You have to sell your ads. You have to physically print the book, box it, warehouse it, ship it, distribute it. All of this takes time. For all I know, it’s based on data from September or October 1885. If the Gardners moved to Georgetown in early 1885, they would have been there and settled when the production on the 1886 City Directory began, then late in 1885 or early in 1886 they moved again, this time to Baltimore.

This seems reasonable. It’s not perfect, and were it not for the evidence of the City Directory I would lean toward dismissing the family lore that my great-grandfather lived in Georgetown as a fable or a false memory. But I have the evidence, and I have to follow the evidence wherever it goes. The evidence proved my conclusion about where Atwell died wrong. What else will it confound?

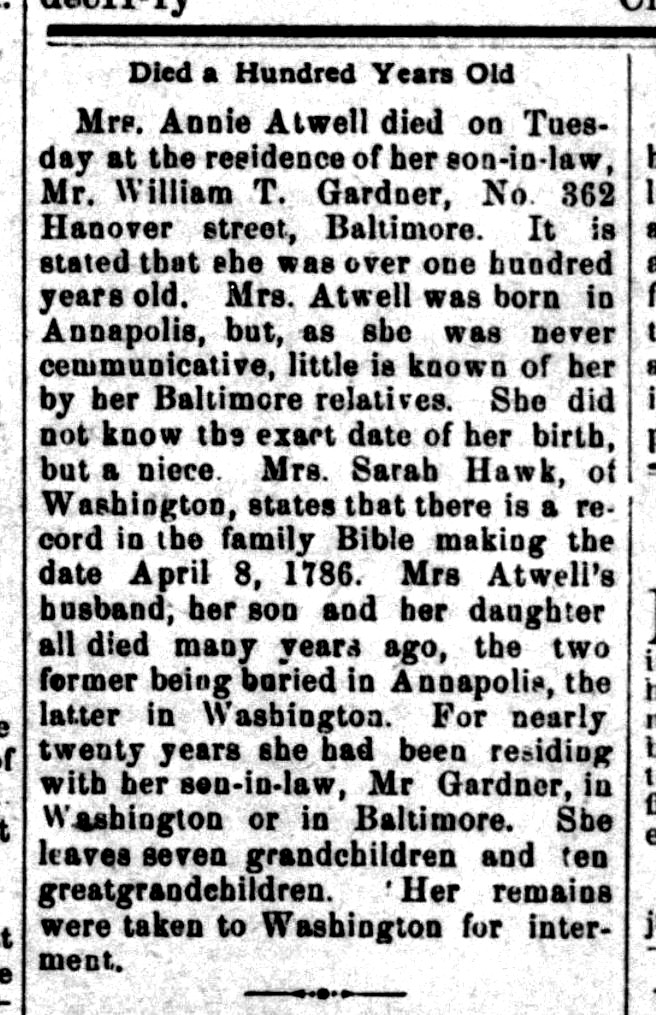

Let’s take a look at The Evening Capitol, published in Annapolis, on June 10, 1886 as well:

The Annapolis article has even more information. A family Bible! A niece, which suggests Atwell had sisters or brothers! Seven grandchildren! Ten great-grandchildren!

And born on April 8, 1786.

Here’s the problem. That strikes me as quite improbable. Because, again, here’s what I know.

Her daughter Mary, William’s first wife, was born in the 1834. She died at the age of 34 in November, 1868. (William would marry my great-great-grandmother Susan, a widow from Baltimore, the following December.) If Anne were born in 1786 and gave birth to a daughter in 1834, she would have been forty-eight years old. Possibly, Mary could have been conceived when Anne was forty-seven. That would put her at the extreme upper limit of female reproductive capacity.

That age also isn’t consistent with the census records of 1850, 1860, 1870, and 1880. Let’s walk through the documentary evidence.

In 1850, Annie Atwell is living in Annapolis with two children, WD (male) and E (female). WD, the son, is said to be 21. The daughter, E, is said to be 16. This would put WD’s birth around 1829 and E’s birth around 1834. E would appear to be William’s first wife, Mary Elizabeth Atwell. WD would appear to be the son who, according to the Evening Capitol, “died many years ago.” Her husband likewise appears to be deceased.

The Census gives Annie’s age as 45. That would put her birth circa 1805. She would have been 24 when WD was born and 29 when Mary Elizabeth was born. If the news reports are accurate, she would have actually been a few days shy of turning 64. (The Census is meant to reflect where people are on April 1st.)

In 1860, we find Annie Atwell in Baltimore. She is living with her daughter Mary and son-in-law William Gardner, along with their two children, Margaret (aged eight) and William (aged five). Also in the household appear to be William’s father William Gardner, trade given as shoemaker, and his wife Charlotte. (I am undecided if she is my great-great-grandfather’s mother. She could be. I have no evidence either way.)

The Census gives Annie’s age as 50. That would put her birth circa 1810. She would have been 19 when WD was born and 24 when Mary Elizabeth was born. Insofar as the Census Bureau is concerned, she aged all of five years in a decade. If the news reports are accurate, she would have been a few days shy of turning 74.

I have made the tentative assumption over the years that WD Atwell died between 1850 and 1860, but as with Charlotte Gardner, I have no evidence either way. Find-a-Grave lists few Atwells in Annapolis, and none match an Atwell with initials of “W. D.”

Annie’s residence with the Gardners in 1860 may have been temporary, however, as the news articles from 1886 about her death say that she resided with William for “nearly twenty years,” which suggests that she moved in with the Gardners in Washington around the 1866-1868 time span. A number of theories suggest themselves to explain this. Perhaps Mary was pregnant in early 1860 and the Gardners needed help. (Either Mary didn’t carry the child to term or it died before 1870. There is a gap of about seven years between William Jr., born about 1855, and Mollie, born about 1862, and I have often pondered the possibility of a grave in Baltimore belonging to a long-forgotten great-great-great-uncle or great-great-great-aunt.) Perhaps when Mary died in 1868 Annie moved in with the Gardners to help William care for his children — the youngest at the time, Ella, would have been two — and stayed. At this distance, it’s impossible to say.

The former raises the intriguing possibility that WD Atwell could have been alive post-1860.

In the Census of 1870, we find Annie in Washington, living with the Gardners — William, his second wife Susan, four children from his first marriage, aged four to eighteen, and two children from Susan’s first marriage, aged five and nine. William and Susan have been married for four months. (Curiously, their marriage license wouldn’t be filed with the state of Maryland for another year and a half.)

The Census gives Annie’s age as 65. That would put her birth circa 1805. She would have been 24 when WD was born and 29 when Mary Elizabeth was born. Insofar as the Census Bureau is concerned, she aged an improbable fifteen years in a decade. If the news reports are accurate, she would have been a few days shy of turning 84.

In the Census of 1880, Annie still lives with the Gardners. Some children have left; William’s daughter Margaret has married and has children of her own, Susan’s son Thomas is in the Navy. Susan’s half-sister Laura Fenhagen lives with them; at this point, Susan is the only remaining family she has. My great-grandfather is seven months old.

The Census gives Annie’s age as 80. That would put her birth circa 1800, the earliest birth year the Census documentation suggests. She would have been 29 when WD was born and 34 when Mary Elizabeth was born. Insofar as the Census Bureau is concerned, Annie has again aged fifteen years in the last decade — and thirty years over the last twenty. If the news reports are accurate, she would have been a few days shy of turning 94.

Here the trail ends. But what we have is a trail of documentation that suggests a birth date between 1800 and 1810, not to mention basic biology that makes a birth date in 1786 a bit unlikely.

And yet, there is the reported evidence of the family Bible which I cannot see and thus cannot confirm.

So when was Annie Atwell born? 1786? Circa 1800? Circa 1805? Circa 1810?

I have no idea. I am skeptical of 1786. It seems improbable to me. Yet, I can’t dismiss it. The reality is that, barring other evidence, I will never know.

However, the newspaper article does provide me with some interesting and useful data.

I now know that Annie Atwell’s husband and son are buried in Annapolis. I don’t know their names. I can’t even guess what WD stands for, though given the times and the unimaginativeness of names in the early 19th-century William seems likely. The husband likely died before 1850. The son, WD, may have died before 1860, but that’s only a supposition. Intuition tells me based on the wording of the Annapolis Evening Capitol article, that he died between his father (pre-1850) and sister (1868).

I now know that WD Atwell had children and grandchildren, thus he may have living descendants to this day.

The Annapolis Evening Capitol article refers to “seven grandchildren and ten greatgrandchildren” as being alive. William and Mary Gardner had four living children as of the 1800 Census — Margaret, William Jr., Mollie, and Ella. Margaret married to a carpenter named William Gordon before 1880 and lived on South Carolina Avenue SE, and they have five children by 1886. (William would died in 1888, and Margaret, though she never remarried, had another child in 1890 who was either a stillborn or died shortly after birth.) William Jr. disappears from history; in fifteen years of searching, I have found no evidence of his fate after the 1880 Census. The only thing I can say of William for certain is that, if he died in Washington, he was not buried in Congressional Cemetery as his parents, grandmother, and three siblings were. Mollie presumably marries in the 1880s and has four children with her first husband, who was either surnamed Barnard or Bernard, as a later Census indicates she had a total of five children, a marriage record in Maryland in 1893 (when she married John Hanson, her first cousin!) indicates she was divorced, and she had a child with either her second husband (the first cousin!) or the third. All I know — or rather, suspect — is that they existed; I don’t know their names, and, like William Jr., I have struggled to find them. Ella, as yet, had no children; her first, named Mary Elizabeth, apparently after her mother, would be born and die in 1890.

So, through her daughter, Annie Atwell had at least three grandchildren and five (and no more than nine) great-grandchildren alive in 1886. Thus, Annie’s son WD Atwell had at least three children of his own (and possibly four) alive in 1886 and at least one (and no more than five) grandchildren alive at that time as well. I have considered the possibility that WD Atwell married and had children over the years. I’ve even pondered the amusing possibility that the actress Hayley Atwell, whose father’s family is American, could be descended from WD Atwell, making some of my distant cousins through my great-great-grandfather Hayley Atwell’s distant cousins as well.

I should note this calculation is not a perfect science. A Baltimore Sun article on my great-great-grandmother’s death in 1902 does the same sort of thing — numbering her living children and step-children — and I have come to believe over the last two years that one of those numbers may be wrong. (For what it’s worth, the step-children number three in that article, which account for Margaret, Mollie, and Ella. Given his complete disappearance, I feel safe in concluding that William Jr. was dead well before 1902.)

Still, despite my skepticism at some of the particulars, these articles reveal the existence of avenues that can be explored. They are enshrouded in the fogs of time and I can’t see them clearly at present, but I know they exist and perhaps someday I will find the map that will lead me down these paths.