While doing some genealogical research in old newspapers — see here — I came across this fascinating piece in the Baltimore Sun of October 26, 1900, copied from the New Orleans Times-Democrat. It’s not just fans of today’s media, like Marvel Comics films and HBO prestige dramas and comic books, speculating about what’s next for their favorite characters. Here’s a Sherlock Holmes fan with an ingenious theory about what really happened in “The Final Problems” — three years before Sir Arthur Conan Doyle wrote “The Empty House.” Misspellings of Moriarty and Gillette are in the original. Discovering the word “infradig” (a British word meaning “demeaning”) was a delight.

He May Reappear.

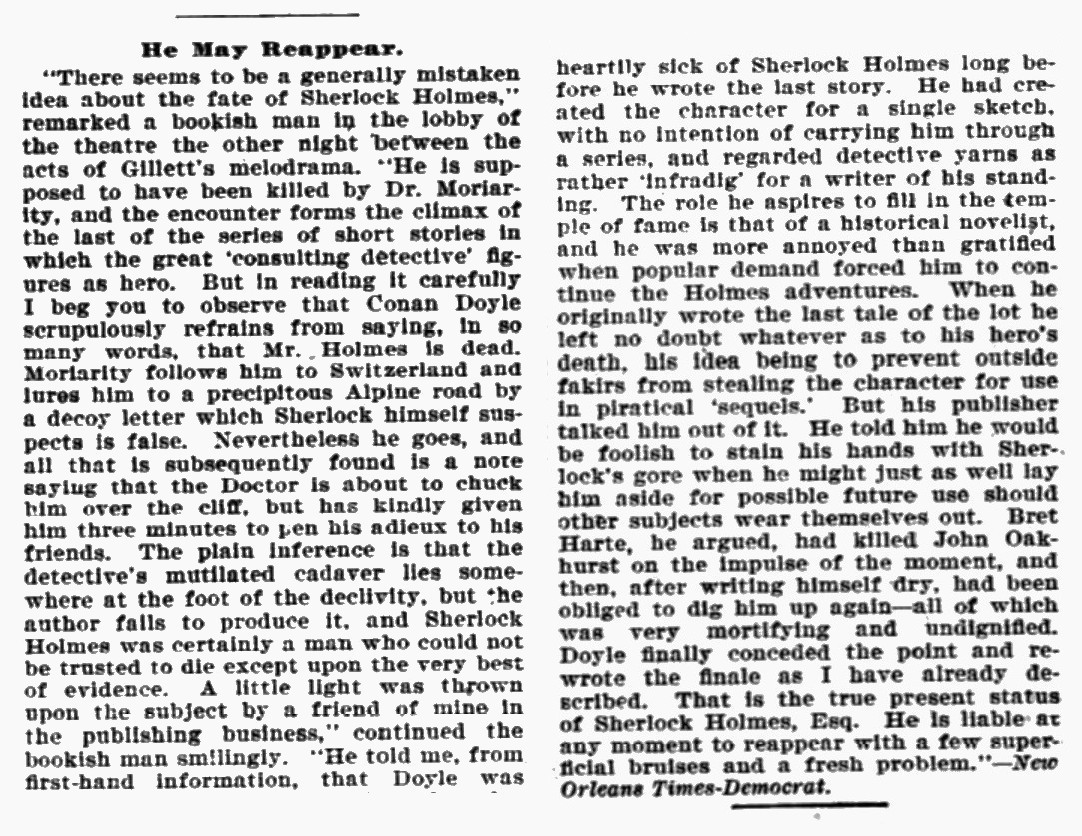

“There seems to be a generally mistaken idea about the fate of Sherlock Holmes,” remarked a bookish man in the lobby of the theatre the other night between the acts of Gillett’s melodrama. “He is supposed to have been killed by Dr. Moriarity, and the encounter forms the climax of the last of the series of short stories in which the great ‘consulting detective’ figures as hero. But in reading it carefully I beg you to observe that Conan Doyle scrupulously refrains from saying, in so many words, that Mr. Holmes is dead. Moriarity follows him to Switzerland and lures him to a precipitous Alpine road by a decoy letter which Sherlock himself suspects is false. Nevertheless he goes, and all that is subsequently found is a note saying that the Doctor is about to chuck him over the cliff, but has kindly given him three minutes to pen his adieux to his friends. The plain inference is that the detective’s mutilated cadaver lies somewhere at the foot of the declivity, but the author falls to produce it, and Sherlock Holmes was certainly a man who could not be trusted to die except upon the very best of evidence. A little light was thrown upon the subject by a friend of mine in the publishing business,” continued the bookish man smilingly. “He told me, from first-hand information, that Doyle was heartily sick of Sherlock Holmes long before he wrote the last story. He had created the character for a single sketch, with no intention of carrying him through a series, and regarded detective yarns as rather ‘infradig’ for a writer of his standing. The role he aspires to fill in the temple of fame is that of a historical novelist, and he was more annoyed than gratified when popular demand forced him to continue the Holmes adventures. When he originally wrote the last tale of the lot he left no doubt whatever as to his hero’s death, his idea being to prevent outside fakirs from stealing the character for use in piratical ‘sequels.’ But his publisher talked him out of it. He told him he would be foolish to stain his hands with Sherlock’s gore when he might just as well lay him aside for possible future use should other subjects wear themselves out. Bret Harte, be argued, had killed John Oakhurst on the impulse of the moment, and then, after writing himself dry, had been obliged to dig him up again–all of which was very mortifying and undignified. Doyle finally conceded the point and rewrote the finale as I have already described. That is the true present status of Sherlock Holmes, Esq. He is liable at any moment to reappear with a few superficial bruises and a fresh problem.”

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle would return to Sherlock Holmes with 1902’s The Hound of the Baskervilles, though that story was set before “The Final Problem” and Holmes’ confrontation with Moriarty at Reichenbach Falls. But this nameless early Sherlockian would be proven true with 1903’s “The Adventure of the Empty House,” in which Sherlock Holmes returns from the dead exactly as he foresaw — he reappeared with a fresh problem and his presumed death shown to be nothing of the sort.